Behind Evelyn Waugh’s comedy is total darkness.

Some authors develop reputations for doing savage things to their characters (Hanya Yanagihara, Hubert Selby Jr.), some for portraying worlds of uncompromising brutality (Cormac McCarthy’s bleak Texas landscapes are some of the darkest places it’s possible for a human to go, and he describes what he sees there in cold, precise, seemingly unfeeling detail), but I think the bleakest moral vision I have ever encountered is in a comic novel: Evelyn Waugh’s ‘A Handful of Dust’.

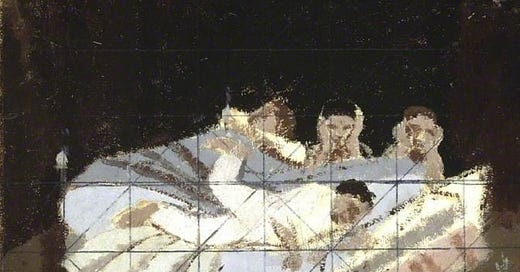

The social scene is the whirl of the aristocratic ‘Bright Young Things’ in 1920s London, his characters are expressions of pure childish desire-gratification, seemingly incapable of moral reasoning. They operate in a void: morality is beyond them, but so is love, beauty, even agency. Nobody really does anything except 'go with the flow'. They are in a sort of primeval state of villainy. The characters understand 'boredom, embarrassment, and even shame but remain absolutely unaware that there is such a thing as suffering'1.

Even intimate tragedy, for instance the death of a young child, is insufficient to penetrate some form of inner life. In Waugh’s novels, utter horrors are described in passing so matter of factly and with such little reflection that it’s hard not to laugh with incredulity (which is sort of the point).

In Waugh’s first published novel ‘Decline and Fall’ (1928), a character describes the world as a spinning wheel we're all placed on. At the centre must be a point that is still, from which presumably one could get one's moral bearings, but no one ever even tries to get there.

The protagonist is Paul Pennyfeather, a young man taking holy orders at Oxford who is found without trousers after being captured by violently rampaging aristocratic yobbos the Bollinger Club. It doesn’t occur to anyone that he is a victim. He is expelled for indecency, and a clergyman tells him ‘I shouldn't be surprised if you turned schoolmaster. That's what most of the young gentlemen do when they're sent down.’

Pennyfeather meekly accepts his fate, and takes a job at a dreadful private school in Wales where the masters are a rouges gallery of misfits and drop-outs. Various misadventures ensue, in which he nearly marries the wealthy and beautiful Margot Beste-Chetwynde, before being set up to take the fall for the secret source of her wealth: A chain of brothels in Latin America. The day before what was to have been the society wedding of the year, he is arrested, but Margot’s alternative husband is a government minister who pulls strings to arrange for Pennyfeather to ‘die’ during surgery. He ends up back at Oxford, claiming to be his own distant cousin, ready to continue studying for the priesthood.

It’s a sort of picaresque jaunt, and it's very funny, but you can’t look at the title without thinking of Gibbon's ‘Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’. Clearly Waugh wants us to laugh, but he also wants us to see how appalling he finds the roaring twenties, how utterly doomed these people are.

I’m currently part-way through an Evelyn Waugh reading project. After ‘Decline and Fall’, I read ‘Vile Bodies’ (1930), ‘Black Mischief’ (1932), ‘A Handful of Dust’ (1934) and ‘Scoop’ (1938). Only ‘Put Out More Flags’ (1942) is left before I reach what I’ve been working towards: Waugh’s supposed masterpiece ‘Brideshead Revisited’ (1945).

I found ‘A Handful of Dust’ so mesmerically brilliant that I struggle to see how ‘Brideshead’ could possibly be better. Perhaps it is, if so it will be one of the best things I’ve ever read, or maybe it will be a case similar to F. Scott Fitzgerald, where ‘The Great Gatsby’ is widely read at school, but ‘Tender is the Night’ is his best book.

I mention all this partly to share my new enthusiasm, but also to recommend the concept of reading projects. People often offer the advice to read widely, across many authors, subjects and eras, and this is definitely sensible, but I think it’s equally important to read deeply. When you find an author or subject you love, to read (over months or even years, with plenty of other things in between) everything by an author, ideally in the order that the books were written, along with biographies, collected letters, influences, criticism, history from the period, etc.

The format of ‘Decline and Fall’, ‘Vile Bodies’ and ‘Black Mischief’ feels very modern. It’s almost a century ahead of its time, with resemblances to spare, modern little novels with scattered elements of scene and character summarised in a telling detail. Little disparate paragraphs surrounded by lots of white space. Think ‘Dept. of Speculation’ (2014) and ‘Weather’ (2020) by Jenny Offill.

‘A Handful of Dust’ is a development away from the total absurdity of Waugh’s earlier novels towards something more grounded and realistic, but he keeps us well removed from his characters' inner lives. 'Waugh does not allow his readers the comfort, however bare, that comes from intimacy with a character's mind but attempts instead to suggest emotion through a precise notation of physical detail.’2 There is acute emotional pain, but the characters are unable to articulate it. When a the protagonist’s son dies, he focuses almost entirely on making the proper arrangements, while musing to a near-stranger how odd it is that several hours ago his son was alive. Waugh doesn't allow us the catharsis of tragedy. He makes us stare into the void, and laugh at the people who can’t perceive it.

Thank you for reading Nine Circles. Sorry posting has been light recently. We’re now shooting for a more realistic bi-weekly schedule.

📚 Currently reading: The Story of Christianity by David Bentley Hart

Legendary chronicler of the media elite Michael Wolff has a fun piece in New York about former CNN chief Jeff Zucker’s probably doomed attempts to buy the group which owns the Telegraph and Spectator. The bid was opposed by basically all the senior editors of both institutions because a big chunk of Zucker’s money was coming from UAE royals.

The Spectator’s chatty Life section at the back of the magazine has had a lot of turnover recently. It’s the part after we’ve got through politics, book reviews and the arts, where the magazine doesn’t so much loosen its tie as pour a whiskey and settle back into an armchair to tell you what it really thinks. I’ve been enjoying some of the rotating cast of new columnists they seem to be trying out for a permanent berth, particularly ‘Charmed life’ by Petronella Wyatt, ‘Foreign life’ by Owen Matthews, ‘After life’ by Damian Thompson and particularly Nicholas Farrell’s ‘Dolce vita’.

The previous issue of 9C asked ‘what even are the humanities?’ Thinking along similar lines, I loved reading Thirteen Ways of Looking at Art by William Deresiewicz in Salmagundi.

I enjoyed this interview with the psychoanalyst and prolific writer Adam Phillips by Sameer Padania for BOMB magazine. He has somehow published twenty-five books despite only writing one day a week (the other four are for seeing patients).

The Swiss Federal Council’s annual photos are incredible. I had no idea about these until very recently, but this has considerably improved my opinion of the government of Switzerland. Truly outstanding soft power work. Presented below are a selection of my favourites from the last few years.

This is a quote from somewhere that I’ve written down in my notebook, but stupidly not by whom or from where it came.

Again, I don’t know where I got this, sorry. Possibly from a PDF on JSTOR that I can’t now find.