In the last decade, the number of enrolments in humanities degrees in the USA has dropped precipitously: Graduate numbers fell by 25% between 2012 and 2020. There’s been a smaller but still meaningful 5% drop in humanities undergraduate degrees taken in the UK, where funding has been slashed brutally.

Some of this in the UK at least is surely a function of our fifteen-year economic stagnation. A brutally competitive UK graduate labour market combined with climbing tuition fees is an incentive for all but the richest students to take more clearly vocational degrees: STEM degree enrolment rates have increased in the same period, though I suspect the two are rarely in direct competition with one another: Students who would have studied a humanities subject are driven into the social sciences, and the more numerate prospective social science students are driven into STEM programmes.

There has also been a change of cultural emphasis over the same period. The current British government is very clear that it wants fewer English Lit. students, and more engineers.

Instinctively, I find this depressing, but the more I try to explain why, the more I find the reasons slip from my grasp.

It’s not easy to even define what the humanities are, exactly. What unifies the study of ancient and modern languages, linguistics, literature, history, law, philosophy, archeology, theology, art criticism, etc., other than that they often share a building on university campuses?

Some pro-humanities partisans make therapeutic or moral arguments for the fields, arguing for arts to take something like the place of religion in society, providing foundational meaning and connection, or suggesting that reading fiction ennobles the soul and is a route to moral character (I would gently suggest that the behaviour of the twentieth century’s greatest novelists encourages a level of scepticism in the idea that reading a lot makes you more likely to recognise that other people have the same moral worth as you).

I’d been struggling with these questions until Wilfred M. McClay’s essay in The New Criterion helped resolve some of this for me. He offers a helpful definition, and suggests that instrumentalist and political arguments about the value of the humanities in the academy have made them less vital, and thus less appealing:

The distinctive task of the humanities, unlike the natural sciences and social sciences, is to grasp human things in human terms, without converting or reducing or translating them into something else—as into physical laws, mechanical systems, biological drives, psychological disorders, social structures, and so on. The humanities attempt to understand the human condition from the inside, as it were, treating the human person as subject as well as object, the agent as well as the acted upon.

To grasp human things in human terms. Yet such means are not entirely dissimilar from the careful and disciplined methods of science, which is also, after all, a pursuit unique to humans. In fact, the humanities can benefit greatly from emulating the sciences in their careful formulation of problems, isolation of variables, and honest weighing of evidence. But the humanities are distinctive, for they begin and end with a willingness to ground ourselves in the world as we find it and experience it, the world as it appears to us, our life-world, our Lebenswelt—the thoughts, emotions, imaginings, and memories that make up our picture of reality. The genius of humanistic knowledge—and it is a form of knowledge—is its kinship with the objects it helps us to know.

Hence, the knowledge the humanities offer us is like none other and cannot be replaced by scientific breakthroughs or superseded by advances in material knowledge. Science teaches us that the earth rotates on its axis while revolving around the sun. But in the domain of the humanities, the sun still also rises and sets, and still establishes in that diurnal rhythm one of the deepest and most universal expressive symbols of all the things that rise and fall, or live and die.

It utterly violates the spirit of literature, and robs it of its value, to reduce it to something else. Too often, there seems to be a presumption among scholars that the only interest in Dickens or Proust or Conrad derives from the extent to which they can be read to confirm the abstract theoretical propositions of Marx, Freud, Fanon, and the like—or Smith and Hayek and Rand, for that matter—and promote the correct preordained political attitudes, or lend support to the identity politics du jour. Strange, that an era so pleased with its superficially freewheeling and antinomian qualities is actually so distrustful of the literary imagination, so intent upon making its productions conform to predetermined criteria. This is why our leading publishers now employ “sensitivity readers,” and feel free to perform surgery on the works of the past, removing their perceived blemishes. Meanwhile, the genuine, unfeigned love of literature is most faithfully represented not in the elite universities but among intelligent general readers and devoted secondary-school teachers scattered across the land.

I highly recommend reading the whole thing.

Welcome to Nine Circles issue twelve. Happy new year!

📚 Currently reading: A Terribly Serious Adventure: Philosophy at Oxford 1900-60 by Nikhil Krishnan.

If you enjoyed reading Nine Circles last year, please do share it with others you think might enjoy it too!

Writing on the Chinese governments increasing efforts to project conservative cultural values at home, Michael Schuman in The Atlantic includes this absolute marmalade-dropper:

In a recent video that went viral on Chinese social media, Jin Canrong, an expert on U.S.-China relations at Renmin University, in Beijing, argued that ‘there is a question as to whether Greece and Rome existed.’ Aristotle, he claimed, is a fabrication: No single person could have written so much on so many topics. Even the writing materials for such a volume of words would have been unavailable in antiquity, he claimed.

I certainly didn’t have Aristotle truthers on my 2024 bingo card.

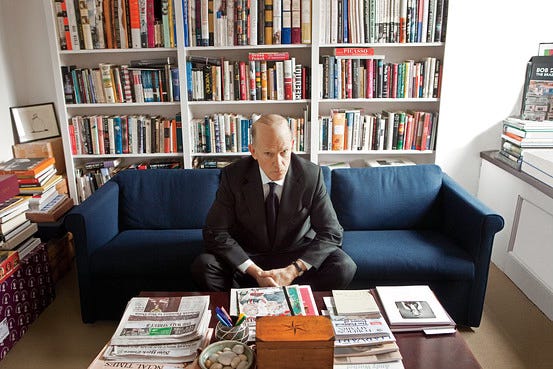

Literary mega-agent Andrew Wylie is on a publicity kick: The consigliere to some of the world’s greatest writers has in the last few months sat for interviews with The New York Times Magazine, The New Statesman and The Times, and participated in a fantastic profile by Alex Blasdel in The Guardian1.

But to what end? He hasn’t, in the decades he’s spent at the top of his game, made a concerted tour of the press like this before. He’s not promoting a book, and I don’t get the impression this is the valedictory performance of a man on the verge of retirement.

But it certainly is a performance of sorts. He’s intimidating even when you’re reading someone else talking to him, even more so when once you see a photo. In the eighties, he was described as a sort of Wall Street figure in the publishing world, but there’s something about him so severe as to be almost funereal. Less ‘the Jackal’, as he is sometimes known, than the Undertaker.

And quite the banker he was, in a sense. In 1990 he took his client Philip Roth away from the independent publishers Farrar, Straus and Giroux when they wouldn’t meet his contract demands. Simon & Schuster gave Roth a three book deal with an advance of $2 million. FSG had been giving him £180,000 per novel.

‘I had lunch with Andrew Wylie,’ said Roger Straus, the President of FSG in an interview with The New York Times that year. ‘He said he could get between $3 million and $5 million for the three books, but that I could have them for $1.5 million. I said that's ridiculous. I told him we paid Philip about $160,000 a book for world rights and they just about break even.’

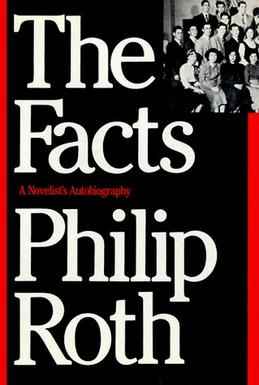

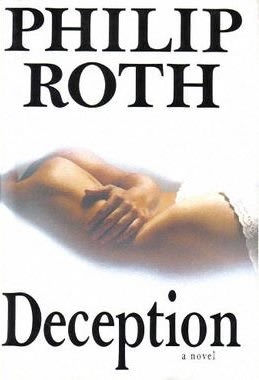

Roth was by this point seen as one of America’s greatest living novelists, but being a writer of great literature doesn’t exactly guarantee a big cheque. Wylie saw the potential to break Roth out of the intellectual-seeming literary marketing FSG had been conducting, and try something with more mass appeal. Compare the covers of Roth’s two previous books with FSG, ‘The Facts’ and ‘The Counterlife’ to the first title in his new three-book deal: ‘Deception’.

'As you can see, the Simon & Schuster approach is as night to day’, Wylie said to the Times’ Roger Cohen2.

Wylie was by this point notorious for demanding (and often winning) massive advances for his clients, who were generally novelists of greater artistic merit than commercial success (though many of them have managed both). Part of his rationale was that the more money a publisher spends to purchase a manuscript, the more they will spending or marketing it to readers.

But he also had two persuasive arguments for their value. First, many authors were undervalued because the rights to publish their work around the world was being undersold by their American publishers, and second that truly high-quality books would continue selling for decades or even centuries to come. To focus on how Roth performed commercially in the first year was ridiculous, Wylie argued. His publishers should pay millions because his books will provide them with a healthy backlist profit each year with very little work required after the initial outlay.3

The figure of Wylie as literary pirate reached its peak in 1995, when Wylie secured a $800,000 advance for Martin Amis, an enormous amount for a British literary novelist at the time. To do so, Wylie had poached Amis from his previous agent Pat Kavanagh, who was not only godmother to Amis’ daughter, but married to his close friend Julian Barnes. The story was too much for the British press, who covered every detail of the drama in obsessive detail, and christened Wylie ‘the Jackal’. The name stuck.

Andrew Wylie was born in 1947 into a patrician New England family. His mother was from a line of bankers, his father was Editor-in-Chief at publisher Houghton Mifflin. It seems almost too obvious and boring to wonder if his financial assaults on the publishing establishments are in a sense attacks against his father. But he clearly had a pretty unhappy childhood: He was expelled from boarding school and spent almost a year in a psychiatric hospital as a teenager before attending Harvard. He spent his twenties driving a cab in New York and taking epic amounts of drugs with punk rock bands and Andy Warhol before deciding at thirty he should probably think about a career and reinventing himself for what wouldn’t be the final time.

The story goes that he won his first client, the investigative journalist I.F. Stone by singing him Homeric verse in Ancient Greek. Already balding, he is reputed to have approached Roth at a party and said ‘I’d give my last hair to be your agent.’ On the phone to Salman Rushdie, he extracted a promise to meet for drinks on the agent’s next visit to London. He flew the next day, phoned again, and asked ‘can we have that drink?’

Stories like this attach themselves to many of Wylie’s acquisitions of clients. One wonders about the role he has played himself in disseminating them. He is clearly a skilled myth-maker, and perhaps this is one of the greatest skills he applies to his authors’ benefit.

On selling Rushdie’s novel ‘The Ground Beneath Her Feet’ to Henry Holt & Company, he insisted that as part of the deal they also re-issue three paperback titles from Rushdie’s backlist, in re-designed matching editions. He, maybe more than anyone, understands how to guide an author’s work towards the status of ‘classic’.

Devastatingly, the two pun titles I’d have wanted to use for this piece ‘Life of Wylie’ and ‘Days of the Jackal’ were both taken already.

I have only read your piece on humanity so far but wanted to say that I found it really enjoyable. To think how we can describe why it is important I find it easier to imagine a world without it. We would have no soul, no anchor and no feeling of humanity in all it later forms.