A note to readers: The footnotes to this essay mainly consist of stupid jokes. If you are reading in your emails, to avoid having to scroll down to the bottom of the page for each footnote, simply click on the title above, and Substack will open in your web browser. You can then tap your screen/hover your mouse over each superscript number to view the footnote without loosing your place in the main text.

The year is 1967, and you are an employee of The Thought Experiment City Trolley Company (Thought Experiment City1 is in the mid-western USA, so what you call ‘trollies’ would be called ‘trams’ or ‘streetcars’ in other parts of the world).

It is early in the morning, and the trollies are not yet open for passengers. As you crest Abstract Hill,2 you test the brakes and to your concern find they aren’t working at all. The trolley picks up momentum until it is hurtling down the steep street at a dangerous speed.

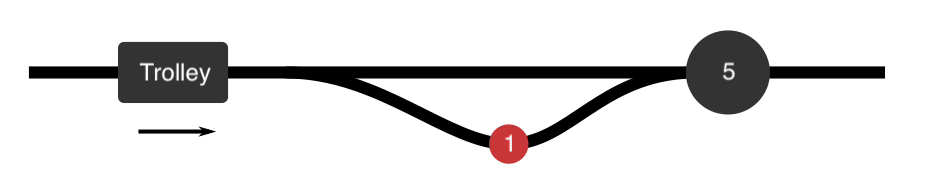

To your dismay, you spot on the track ahead of you five maintenance workers. They have neither seen nor heard the trolley approaching, and you have no doubt that if you don’t take action they will all be killed.

At the last second, to your relief, you see that there is another track on to which you can steer the trolley. But the relief lasts only a fleeting moment: There is also a lone maintenance worker on this track.

You have not yet touched the steering wheel. Should you yank it to the right and thereby kill the lone worker, or fail to interfere and by your inaction allow five men to die?

How about this:

You are a doctor in Mach Hospital.3 The lives of five of your patients could be saved by the manufacture of a certain gas, but the process of concocting the gas will inevitably release lethal fumes into the room of another patient whom for some reason we are unable to move.

Should you manufacture the gas which would save five lives, even though doing so will mean discharging lethal fumes into the room of another patient?

Or this:

You are about to give a patient a massive dose of a life-saving serum which is in short supply. Giving him a smaller dose would result in his death. Just as you’re about to jab needle into arm, a nurse runs into the room and tells you five more patients have arrived, each of whose life could be saved by one fifth of the dose you were intending to give your first patient.

You hesitate. Can you tell the patient in front of you that you now no longer intend to save their life after all?

Or this:

You are a surgeon elsewhere in the hospital, with five dying patients, each desperately in need of a rare serum that can only be obtained from the Hypothetical Gland of people with ABC blood type. On your operating table is such a person. You can press a button and a machine will extract the serum from the gland, which can then be used to save the lives of all five other patients, but in draining the gland you will kill the donor.

They are perfectly healthy. Should you kill them to save five others?

Or finally, this:

You are part of a group exploring caves underneath the city. Ahead, one of your companions has become utterly stuck in a narrow gap between rocks, blocking the only exit. Behind you the caves are quickly flooding. You have tried everything to dislodge the stuck caver, but nothing can be done, and the five other members of your group will drown if you don’t squeeze through the gap in which he is stuck very soon. Fortunately, one of your number has a stick of dynamite. Setting aside for now your questions as to where they got it and what on earth they were intending to do with it, you could detonate the dynamite next to the stuck caver, thereby killing him but creating space for the greater number to escape death by drowning.

Should you kill your companion so the other five of you can escape with your lives?

I think most readers would feel intuitively that it is better to turn the trolley and bring about the lone worker’s death to save the five, and would give the vaccine in smaller doses to five patients rather than one massive dose to the original patient. In extremis, you’d probably consider killing the stuck caver if it meant ensuing five others escaped the rising waters. But you probably wouldn’t concoct a life saving gas for five hospital patients if it meant the fumes would inevitably kill someone in another room, and you wouldn’t harvest serum from the gland of one healthy patient to save the lives of five others.

Why are there some circumstances where it seems morally permissible to kill one person to save many, but others where it seems morally abhorrent?

This is an essay about the search for objective moral truth.

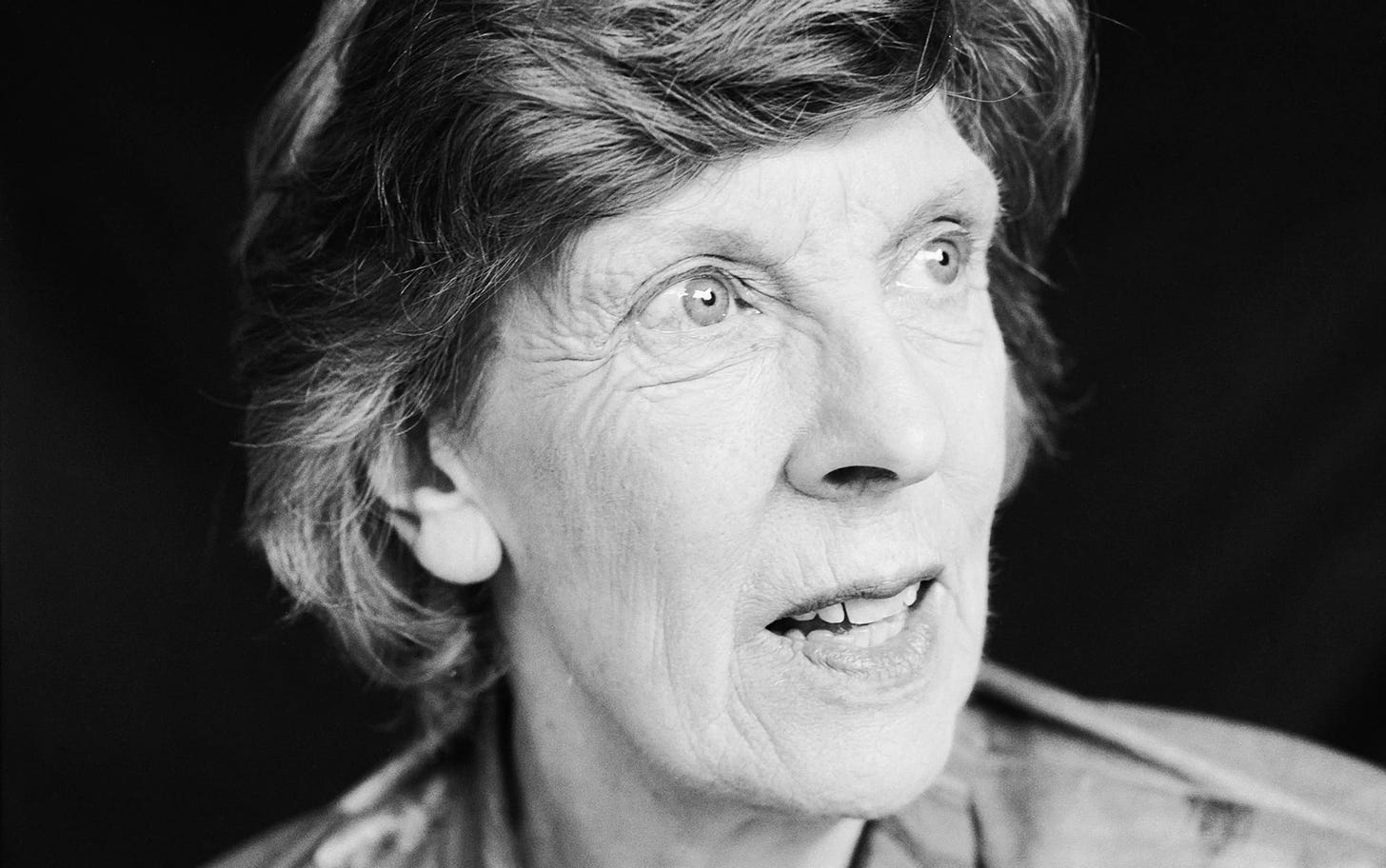

The first of those examples is a classic thought experiment known simply as ‘the trolley problem’. It was first proposed in an Oxford Review paper from 1967 by the moral philosopher Philippa Foot, titled ‘The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect’.

The trolley problem is often presented out of context as a fairly crude example of utilitarian decision making, but in Foot’s original use it was part of a series of examples she provided to analyse why we judge some actions as permissible and others as impermissible, even when they result in the same amounts of benefit and harm.

Foot’s antagonist in the essay is the ‘doctrine of double effect’, a rule used by Catholic thinkers to describe the limited circumstances in which abortion may be permitted, but which secular philosophers had also found useful and started to apply to a range of other moral dilemmas.4 The doctrine is concerned with intention: It tries to distinguish between harms that are intended as the means to an end (which it deems impermissible), and harms that are merely foreseen but unintended side effects (which it allows in some cases).5 Foot argues that this distinction between intended and merely foreseen consequences is not as morally relevant as its proponents believe.

The classic example of the doctrine in action is of a pregnant woman with a life-threatening condition like cervical cancer. The intended effect of a hysterectomy would be to remove the cancer and thereby save the mother’s life. A consequence which is foreseen but not intended is the death of the foetus. Under the doctrine, that would be permissible, while an action where the principal intention was the death of the foetus rather than the saving of the mother’s life would not be allowed.

In the trolley scenario then, if you turn onto the track with one worker, their death would be a foreseen but not intended consequence of saving five other lives.

A major part of Foot’s paper is dedicated to examples of situations where the doctrine would give us answers which seem to clash with our moral intuition: For instance, the hospital-gas case above. The decision to manufacture the life-saving gas, even though you know this will result in the death of another patient, would likely be permitted by the rule because the death of the one patient is not directly intended, but merely a foreseen but unintended effect of trying to save the five. A moral system that can’t differentiate between that and the trolley scenario, she argues, is ridiculous.

Foot also suggests it is difficult to define precisely the difference between directly and obliquely intended harms. For instance we could suppose ‘that the trapped explorers were to argue that the death of the fat man might be taken as a merely foreseen consequence of the act of blowing him up.'

Equally, one event could even be described in different ways and desired under one description and not under another, or the direct and oblique intentions can be so close that the distinction is meaningless: Our direct intention is to move his body from the mouth of the cave by explosion, the oblique intention is killing him.

As Foot concludes her argument, she zooms out from the doctrine to argue more generally against the idea that intention is the best way to judge the morality of an action. She argues that the key distinction lies in the difference between negative duties (to refrain from harm) and positive duties (to render aid). Negative duties are generally seen as more stringent than positive duties (it is worse to harm someone than to fail to help them, she thinks). These principles explain our common intuitions about the cases. The surgeon would be violating a negative duty by actively killing one, which is not justified even to save five. The trolley driver, however, faces a choice between two negative duties (killing one or five) and so should choose the lesser harm.

Philippa Foot was born in 1920, the daughter of a Yorkshire industrialist and the maternal granddaughter of President Grover Cleveland. She was brought up at Old Hall, Kirkleathem, ‘in the sort of milieu where there was a lot of hunting, shooting, and fishing, and where girls simply did not go to college’. She was raised by a series of governesses more concerned with inculcating proper manners than educating their charge, but when she was in her later teens one suggested she might go to university. ‘At least she doesn’t look clever’, a friend consoled her mother. She studied for the entrance exam via correspondence courses, and went up to Somerville College, Oxford in 1939.

War had started to make Oxford strange, many dons and male undergraduates were either drafted into the officer corps or otherwise contributing to the war effort. After finishing her degree, Foot spent the rest of the war working as an economist in Whitehall, sharing a flat in London with Iris Murdoch (they had been undergraduates together, and would become lifelong friends). When the war ended, she returned to Oxford to teach philosophy to PPE students.

By then the dons who had left for the war effort were returning, and recommencing the active debates which had transformed philosophy at Oxford over the previous twenty years.

Men like Gilbert Ryle and J.L. Austin6 believed philosophy had been 'too apt to infer from the clothing of our language the existence of a spectral universe of invisible things'. For instance ‘the king ordered the prisoners be executed’ and ‘the king ordered justice be done’ would make us think there is a ‘thing’ called justice in the same way that there is a ‘thing’ called execution. Many problems of philosophy, they thought, would simply dissolve when language was properly scrutinised like this.

They were building on the work of G.E. Moore & Bertrand Russell, who were interested in the specificity of language and reducing it to formal logic, which Russell experienced as like ‘watching an object approaching through a thick fog: at first there is only a vague darkness, but as it approaches articulations appear and one discovers that it is a man or a woman, or a horse or a cow or what not'. They wanted ‘to scrape away at sentences until the content of the thoughts underlying them was revealed’. Ryle’s innovation was to focus his work on analysing ‘why is this expression nonsense, and what sort of nonsense is it?’

Into this form of philosophy stepped Foot’s two main antagonists: A.J. Ayer and R.M. Hare. Ayer was colourful figure who, having studied with the Vienna Circle prior to the war, popularised Logical Positivism in the English speaking world. His immensely popular book Language, Truth and Logic was an attempt to answer the question ‘from where can knowledge be derived?’ All knowledge must either be analytic (true by definition - tautologies such as ‘all bachelors are unmarried men’) or verifiable by sense data. Ayer believed that moral statements described no facts. More than simply not being true, he argued it was impossible even to have a meaningful conversation about morality. It was literal nonsense.

Unlike Ayer, R.M. Hare did think it possible to talk meaningfully about moral problems, but he did not think moral judgements are grounded in objective moral facts independent of our judgements. He argued that one could rationally discuss moral laws if they were prescriptive (ie. ‘do not murder’) and universalisable (ie. ‘murder is always wrong’).7

It was into this world that news came of the holocaust.

This was the formative moment for Foot: She simply could not accept that to call the holocaust evil was nonsense, or that she would merely be expressing a different preference to the Nazis. 'In the face of the news of the concentration camps,’ she wrote much later ‘it just can’t be the way… Ayer and Hare say it is, that morality in the end is just the expression of an attitude, and the subject haunted me.’

Her lifelong project became to demonstrate that secular philosophy could speak of objective moral truth.

Foot’s first important work in this direction were two papers published in 1958, titled ‘Moral Arguments’ and ‘Moral Beliefs’ (the first published in Mind, the second in Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society).

In ‘Moral Arguments,’ she dissects how moral arguments work and provides a detailed example, using the concept of ‘rudeness,’ to show how there can be strict logical connections between factual premises and moral evaluations.

She argues that the concept of rudeness necessarily involves causing offence by indicating a lack of respect. Therefore, if someone accepts the factual premise that a certain behaviour causes offence by indicating lack of respect (let's call this premise O), they cannot consistently deny that the behaviour is rude (conclusion R). To deny R while accepting O would be to misuse the concept of rudeness. Foot argues that ‘it is impossible for him to assert O while denying R.’ This shows that there can be strict logical connections between factual premises and evaluative conclusions. Foot then suggests that similar logical connections might exist for moral concepts, challenging the view that there is always a logical gap between factual premises and moral conclusions.

In ‘Moral Beliefs’ Foot argues from another angle that concepts like 'good' and 'virtue' are not purely subjective or arbitrary, but that they have an internal connection to their objects that limits how they can be applied. Just as we can't arbitrarily call anything an 'injury,' we also can't call just any action 'good' or 'virtuous'. Concepts like virtue, she tried to persuade her readers, are meaningfully tied to human needs.

These arguments are much more about demonstrating that we can meaningfully talk about morality than proving that morality itself is a set of objective facts. That’s where Foot wanted to get to, but she worried it might be beyond her to find a way. For a time, she nearly abandoned the project as hopeless. Instead, having left Oxford to lecture in California, she threw herself into practical ethics and particularly the then highly charged question of abortion. This was when she wrote ‘The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect’.

You awake in your apartment near Aristot Hall, the prestigious opera house in downtown Thought Experiment City. You roll over, and are bewildered to find lying next to you an unconscious violinist. A very famous unconscious violinist. As your faculties begin to return after sleep, you realise there are other figures in the room. They introduce themselves as members of the Society of Music Lovers. They tell you that the great violinist has a fatal kidney ailment, but due to his great talent they cannot allow him to die. They therefore stole the city’s medical records and found there was only one person who had the correct blood type to help.

Last night, they say, the Society kidnapped you, and plugged the violinist’s circulatory system into yours so that your kidneys can cleanse his blood as well as your own. The Society members explain that after about nine months of this, the violinist’s kidneys should have recovered well enough that you two can be separated again. They wish you a good day and leave.

Naturally, you go to Mach hospital, where the doctor says 'look, we're sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you - we would never have permitted it if we had known. But still, they did it, and the violinist now is plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it's only for nine months.’

Would it be reasonable to unplug yourself, knowing it would kill the violinist? Or does he have a moral right to use your body to survive?

‘The unconscious violinist’ problem was first proposed by Judith Jarvis Thomson in her 1971 essay ‘A Defence of Abortion’ in Philosophy and Public Affairs.

Thomson would become one of the central intellectual voices in the American abortion debate. In ‘A Defence of Abortion’ she grants for the sake of argument that the foetus is a person and therefore has a right to life, but attempts to demonstrate through a number of thought experiments that even if a foetus has the same moral rights as a full human, a right to life does not always imply the right to use someone else’s body to survive.

But she published another paper on a moral problem with implications for abortion, euthanasia, and all sort of questions of legal responsibility: Is killing worse than letting die? A paper where she discussed and expanded the trolley problem.

In 1976, Thomson published ‘Killing, letting die, and the trolley problem’ in The Monist, creating several variants of the problem that are now considered classics.

Start with this:

You are the only passenger on a trolley in Thought Experiment City, sat on a bench near the driver, watching the sunrise as the vehicle crests a hill and begins to roll down. ‘The breaks have failed!’ exclaims the driver, who then promptly dies of a heart attack. The trolley hurtles down the hill, and you see it is headed towards five workers, who will all be killed if the trolley continues on its path. On another branching track is one worker. You realise you could grab the wheel and turn if you wanted to.

The distinction of the passenger making the decision rather than the driver in Thomson’s first example is important in the light of Foot’s conclusion about negative and positive duties. Thomson points out that the driver was already responsible for the movement of the trolley, so his choice is between the negative duty to refrain from killing five people and the negative duty to refrain from killing one person. But the passenger had no role in events up to the point of his decision, so for him the choice is between the negative duty to avoid killing one and the positive duty to save five: A completely different proposition, much more similar to the dilemma faced by the surgeon. But Thomson thinks that it would be permissible to turn the trolley here too. So why can we do that, but still not kill one person on the operating table to save five other lives? In that scenario, aren’t we also balancing the positive duty to save five lives against the negative duty to avoid killing one?

How about this:

You are stood on a footbridge over the tracks on the hill. You know trolleys, and can see that the one approaching the bridge is out of control. There are five people working on the tracks. But there isn’t another track to turn on to. You know that the only way to stop the trolley is to throw a heavy weight into its path such that it will be derailed. ‘But the only available, sufficiently heavy weight is a fat man, also watching the trolley from the footbridge.’ You could shove the fat man off, killing him and stopping the tram, or refrain from doing so and let five people die for the cost of one life.

Now this seems a lot more like the surgeon’s problem.

Thomson proposes that what matters morally is not simply whether an action involves killing or letting die, but rather whether one is redistributing an existing threat or introducing a new one, and whether one acts on the threat itself or on a person.

She returned in 1984 with a paper simply titled ‘The Trolley Problem’ (Yale Law Journal), in which the ‘loop’ variant is proposed:

You know how it works by now: The trolley is hurtling down the hill towards five workers, you’re stood by a switch and can divert it onto a different track. But this time, after the point of the lone worker on the second track, it loops back to the main track prior to the point where the five are working. You know that if you divert the trolley to hit the one man, it will derail. It is this that will save the five.

Thomson argues that if we believe it's permissible to turn the trolley in the basic case because the one person's death is a side effect of saving the five rather than the intention of our action, then we should judge it impermissible to turn the trolley in the loop case. This is because with the loop, the one person's death is a tool for saving the five. If they weren't there to stop the trolley, it would loop back and kill the five anyway.

In this scenario, Thomson writes, ‘I do not find it clear that the bystander may proceed in this case.’ But ‘many people to whom I have put this case say that the agent may proceed.’ We’re starting to encounter trolley scenarios in which intuitions differ.

In 2008 Thomson published a final paper, ‘Turning the trolley’, (Philosophy and Public Affairs) in which she changed her mind on the solution to the trolley problem: She offered a third option, that the person at the wheel could deliberately crash the trolley or the bystander could throw themselves in front of it, knowing that they would die but that all others would be saved. If you wouldn't take this action, why would you think it's acceptable to turn the wheel to the track with one man on it? Thomson contended that even if the third option isn’t physically available, the bystander still cannot justifiably choose to turn the trolley and sacrifice one to save others if he wouldn’t choose option three were it available. ‘Since he wouldn’t himself pay the cost of his good deed if he could pay it, there is no way in which he can decently regard himself as entitled to make someone else pay it.’

Thomson acknowledged that this goes against common intuitions, but suggested these intuitions may be based on psychological factors rather than moral truths. This gets at an important point about trolley problems and indeed all thought experiments: They exist to focus our instincts, rather than to prove anything in themselves. Daniel Dennett called them ‘intuition pumps’ and that’s what we’re doing here: Pumping intuition in controlled environments to see how it behaves.

Foot returned to her grand project of finding a way to demonstrate that secular philosophy can speak objectively about morality with a paper which she later completely disavowed. ‘Morality as a system hypothetical imperatives’ (The Philosophical Review) was highly influential, but during the final stage of her career she expressed horror at the very thought of the arguments therein.

The issue broached was the ‘is-ought problem’ first described by David Hume in the eighteenth century. Hume wrote that all systems of ethics seem to progress from statements about what is to statements about what ought to be, without any satisfactorily logical way to get from one to the other. Foot danced around this problem in her paper. Kant’s famous notion, she wrote, was that morality is based on ‘categorical imperatives’ - unconditional moral rules that apply in all circumstances, such as ‘never lie.’

Instead, Foot proposed that moral statements are ‘hypothetical imperatives’. These are conditional statements that take an ‘If...then’ form. A simple example would be: ‘If you want Pringles, then you should go to the shop before it closes.’ The imperative to go to the shop only applies if you actually want Pringles. Otherwise, there's no reason to follow it.

Foot suggested we could formulate ethical principles in a similar way. For instance: ‘If you care about the wellbeing of your loved ones, then you should act in ways that promote their happiness and safety.’ Such principles don’t claim to be universal moral laws. She looks at various ways one might try to categorise moral imperatives from other sorts of imperative, but finds them all unsatisfactory.

One advantage of hypothetical imperatives is that they can be evaluated as true or false based on whether the proposed action really does lead to the desired outcome. They don't require us to derive ‘ought’ statements from purely factual ‘is’ statements.

It’s worth reflecting how radically limited a view of morality this is. Most of us who believe in the concept of moral obligations don’t think of them as predicated on whether or not you share a certain desire. Foot thought she had found a way that moral principles could be meaningfully talked about, but in the process demonstrated that disinterested moral behaviour wasn’t a requirement for all people, only those who cared about others.

After many years lecturing at UCLA, Foot returned to Oxford upon her retirement from teaching in 1991. She focused herself on an ultimate solution to her problem, and fifty years after she started publishing philosophical papers, her sole book was published in 2001.

The introduction to ‘Natural Goodness’ mentions Wittgenstein’s notion that it is difficult to do philosophy as slowly as one should. At the launch party, Foot’s editor quipped ‘that is a problem Philippa seems to have solved.’

Finally, she thought, she had found a conception of morality that avoided both supernatural sources of value and the naturalistic view that moral statements are mere personal preferences lacking any objective basis.

She argued that we should think of ‘goodness’ in a human in the same way that we think of 'goodness’ in a tree or a fox. It must be grounded in the qualities which we can factually say will enable it to flourish. That children must be cared for to flourish, for instance, is true regardless of whether one likes children or not.

If we can agree on what characteristics are essential to this understanding of human flourishing, we can agree on what we mean by ‘good.’

Philippa Foot died at home in Oxford in 2010, on her ninetieth birthday.

The beauty of the trolley problem is that it’s probably impossible to propose a rule that can fully capture the complexity of our moral judgments across all the possible scenarios. It has driven some people slightly mad, or at least driven them to create ever more unhinged versions (and recently, ever more unhinged memes).

I was at an event with the ambitious title ‘what is the basis of ethics?’ last night, where the speaker touched on all this in passing, and said something like ‘we philosophers have a term for people who spend all their time minutely adjusting their thought experiments in ways that would never occur in the real world: Trollyologists.’ I don’t think it was meant to be a compliment.

But the problem has captured the mass imagination maybe more than any other thought experiment in modern history. There is a subreddit with eighty-two thousand members, an episode of The Good Place (season two, episode six), and somehow twenty-seven million hits for ‘the trolley problem’ on Google. In 2017, a guy on YouTube tried to put unsuspecting people in trolley problem scenarios in read life (most didn’t pull the leaver, but I think that tells us more about reactions under stress than it does about what the right thing to do was).

One area researchers have found fruitful is psychologically segmenting responses to the scenario (men are significantly more likely to say they’d push the fat man), but I’m not sure how much these tests really tell us. What we’re measuring when you just put the problem to a random person without laying out the context is their moral intuition. Though isn’t that something that was crucial in the first place? Foot was pointing out that in these scenarios we can find how moral systems clash with our intuitions about what ought to be right. But at no point does she explain why she’s so sure that her intuition is correct in the first place, rather than the system that contradicts it.

Equally, it’s possible to imagine devising a rule that fits ones intuition in all scenarios. But even then, we’d have a problem if we couldn’t explain why it was morally right beyond just feeling that it fits. All this effort is being expended to find a rule that matches our instincts, but ideally we should be able to explain why those instincts are themselves morally correct.

A final thought experiment, first proposed by Jason Millar in 2014:

‘You are travelling along a single lane mountain road in an autonomous car that is fast approaching a narrow tunnel. Just before entering the tunnel a child attempts to run across the road but trips in the center of the lane, effectively blocking the entrance to the tunnel. The car has but two options: hit and kill the child, or swerve into the wall on either side of the tunnel, thus killing you.’

How should the car be programmed to react?

Notebook

After I started researching this post, I began to imagine doing a series featuring the history of a different thought experiment each time. It would be called something like ‘Welcome to Thought Experiment City.’ Literally later that same day, the New Statesman published the first in a series of columns about thought experiments by the author and philosopher David Edmunds. Here is his take on Thomson’s unconscious violinist. Clearly he and I are now in direct competition.

Before becoming an academic, Thomson was in advertising. So, I was surprised to learn recently, was the author Salman Rushdie, who apparently invented the slogans ‘Irresistibubble’ for Aero chocolate and ‘Naughty But Nice’ for Cream Cakes (he, if you don’t remember, had to live in hiding for many years after 1989, when Ayatollah Khomeini called for him to be murdered because of his novel 'The Satanic Verses’).

Rushdie’s been on my mind since I listened to the BBC Radio 4 extracts from his moving new book ‘Knife’, the narrative of which is framed around his recovery from a brutal stabbing several years ago. After, I listened to an interview he gave with the New York Times’ Ezra Klein. I highly recommend it. This quote in particular stuck with me:

‘After The Satanic Verses, for a long time nobody wrote about me as a funny writer. It was as if because the thing that had happened to me was not funny, that was kind of dark and obscurely theological, I must also be dark and obscurely theological. It was as if the characteristics of the attack were transposed onto the person being attacked.’

Julian Baggini wrote a brief column on Foot’s career and ‘Natural Goodness’ when it was published in 2001. He mentions how touchingly modest she was, and importantly how a career in academia like hers would be impossible today:

Her brand of philosophy is sadly rare in an academic culture that rewards what Owen Flanagan has called ‘Rubik’s cube minds’. ‘I have a certain insight into philosophy, but I’m not clever at all,’ Foot told me. ‘I often don’t find arguments easy to follow.’ She kept her intellectual eye on the perennial issue at stake, not on what everyone else happens to be saying right now. ‘I don’t read a lot, and I can’t remember all these books and all their details,’ she said. ‘I have a terrible memory and I don’t do it in quite the way clever people who have very good memories and are splendid scholars do it.’

No one in today’s academic culture of performance metrics could have a career like Foot’s. ‘I didn’t ever have to publish. In fact in those days I think people asked those who published a lot why they did so.’

For the first time since 2003 an election for the Chancellorship of the University of Oxford is underway. Voting will be online rather than in person for the first time, which I think is rather a shame. Previously, all fellows and alumni of Oxford were eligible to vote, but had to do so in person and in full academic dress. I imagine the sight of thousands of former students descending on the city in their gowns and mortarboards was quite spectacular.

The role goes back to 1224, when Robert Grosseteste, one of the fathers of English science, was appointed to lead the theological college. Since 1933, there have only been four holders of the office, which has traditionally been for life. The incumbent, Lord Patten, is retiring at 80. As of this election, there will be ten-year terms of office. Patten is a fascinating sort of figure in that one can follow the last forty years of British history and the trajectory of its old elite solely through his life and career: Over the last few decades he’s managed to get himself appointed as the final British Governor of Hong Kong, Chancellor of Newcastle University, Chair of the BBC Trust, Chair of the Conservative Party and European Commissioner for External Relations (effectively the EU’s Foreign Secretary). He was the Conservative MP for Bath between 1979 and 1992, when as party chair he masterminded a strategy that gave John Major a surprise victory but lost his own seat.

Patten’s predecessor from 1987 - 2003 was Roy Jenkins, the Labour former Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary. From 1960 - 1986 it was former Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. From 1933 - 1960, the role was held by Edward Wood, better known as the Earl of Halifax, who managed to do the job while also being by turns Foreign Secretary, Leader of the House of Lords, and Ambassador to the United States. He had previously been Viceroy of India.

Candidates this time around include Lord Mandelson, the New Labour impresario, Lord Hague, the former Conservative Foreign Secretary, Imran Khan, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan (who is campaigning for the job from jail near Islamabad), and former conservative-ish Attorney General Dominic Grieve. The leading internal candidate seems to be Lady Angiolini, who is currently Principal of St. Hugh’s, one of federation of colleges of which the University comprises (previously she had been Lord Advocate of Scotland and Solicitor General, two of the most senior posts at the Scottish Bar). There is also Alastair Bruce of Crionaich, whose main qualification seems to be that he’s comedically posh and has some sort of heraldic role called ‘Fitzalan Pursuivant Extraordinary’.

If Lady Angiolini were to win, she would be the post’s first woman. If Lord Hague were to, he would be its 36th ‘William.’

As it stands, I’d put my money on Mandelson, who has a big interview in Saturday’s Times setting out his stall. His name had also been whispered as in contention to be appointed as the next British Ambassador to the USA, but he has apparently made it known that he isn’t putting himself forward for that role, which suggests to me he at least thinks he’s in with a decent shot.

If you’ve made it to the end of all of this, thank you so much for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this, please do subscribe! Each new reader is a massive morale boost.

Dan x

Many visitors ask, while making use of the generally very safe public transport network, how this small Midwestern city came to have such a strange name. There’s no grand tradition of the city fathers founding the settlement on particularly abstract principles. The truth is, the first settlers of the hills that would eventually take this name were two Danish migrants, Jørgen Thot and Morten Spiermann. What was at first a township known as Thot-Spiermann became anglicised as it grew. By the time it was granted city status by the State of Indiana, the descendants of the Danes were far outnumbered by migrants from northern England. Unable (or perhaps unwilling) to pronounce Thot-Spiermann, it became known by its current name.

Named for Mayor Günter Abtracht. First elected in 1910, he changed his family name to Abstract shortly after the outbreak of the First World War.

Named after Austrian physicist and philosopher of science Ernst Mach, who coined the term ‘thought experiment’ in 1833. Because the residents of Thought Experiment City do have a sense of humour about the whole name thing.

Foot doesn’t take a direct position on the question of abortion in her paper, but I think it’s safe to assume she was to some extent pro-choice.

The roots of the doctrine are in the thinking of Thomas Aquinas, who Foot thought ‘one of the best sources we have for moral philosophy’ and ‘as useful to the atheist as to the Catholic or other Christian believer’.

Austin was a Lt. Colonel in military intelligence during the war, where he played a major role in planning the allied invasion on mainland Europe. Previously, he had led an enormous project trying to map the totality of the axis military resources and chain of command. He once commented with slightly unnerving eagerness that if there was to be another war, he’d like to do something with logistics and supply.

This argument led to the devastating critique that 'everyone should hop on one foot on Tuesday at noon' would count as a moral principle under Hare’s criteria. The ridiculousness of this example is nearly as damaging as an anecdote about Plato in his biography written in the early 3rd century by Diogenes Laërtius, that Plato speaking to a group of Athenians, defined a human as a featherless biped animal. Diogenes of Sinope stood at the back of the room, held aloft a plucked chicken and shouted 'behold Plato's man'.

A thoroughly interesting read about a philosopher I’d never heard of before!

I will also certainly be paying Thought Experiment City a visit. Do they happen to have a quantum vet? I have to see a man about a cat in a box 🤔

Great write up - thanks for putting the trolley problem in context. I did not think I'd be this interested in how it came about!

Minor typo - "...harvest serum from the glad..."