Eike Schmidt, the German art historian and former director of the Uffizi1 Gallery, is the Italian far-right’s candidate to be Mayor of Florence. I found this intriguing because it was so far outside my pre-conceived notions of political identity. It is, for instance, impossible to imagine German art historian and former director of the British Museum Hartwig Fischer running as the Farageist Reform UK candidate for Mayor of London.

The election is due to take place on the 8th and 9th June. Here is a useful guide to the candidates on english-language news website The Florentine if anyone wants to join me in following this election for the next month.

My assumptions about how right-wing politics in Italy work were further scrambled by reading that Schmidt, who is running as an independent backed by Giorgia Meloni’s far-right Fratelli d'Italia (FdI) party along with their coalition partners Lega and Forza Italia (FI), did some fairly progressive-sounding things during the eight years that he lead the Uffizi. He hosted an exhibition exploring violence against women, and a series of exhibitions dedicated to historical female artists like Lavinia Fontana, Italy’s first female professional painter. He also lent parts of the collection to other museums in Tuscany, under the rubric of ‘Uffizi diffusi’ or ‘Diffused Ufizzi’ in order to share the benefits of tourism more widely in the region beyond Florence.

Schmidt has described himself ‘more as an Aristotelian centrist2 than a representative of the right’, which adds further murk to the water. Why would he be running with the banner of the FdI behind him?

I think this has to be viewed through two prisms: First, several years of tension between Schmidt and the incumbent Partito Democratico (PD) Mayor Dario Nardella, and second, the increasing possibility of a candidate of the right actually winning in Florence.

The city has had centre-left mayors since 1985, most recently two five-year terms for Nardella, who is standing down. His predecessor was Matteo Renzi, who resigned when he won the Prime Minister’s job in 2014. This March, a poll had the PD’s candidate Sara Funaro ahead by eight points, but this is a much smaller gap than previous elections (the right has never won more than a third of votes in the city), and FdI-backed candidates have recently won in several other Tuscan seats previously seen as strongholds of the left.

I wonder if this is more a marriage of mutual convenience than an ideological union. Meloni’s government gets the chance to give the PD a bloody nose, and Schmidt gets the institutional backing to mount a serious challenge to a party that he thinks has mismanaged his adopted city for years.

Fratelli d'Italia is in some ways a post-fascist party, a successor to many of the ideological currents of Italy’s fascist era, but since her election victory in 2022, Meloni has proved a smart political operator, binding to her coalition Forza Italia, the moderate conservative party formerly led by Silvio Berlusconi, and has dropped her previous pro-Russia rhetoric, winning some room to manoeuvre with the EU. While Meloni has filtered her national populism through a degree pragmatism, Schmidt has at times played to the crowd during his term at the museum. When part of the Uffizi facing the Arno river was defaced by vandals several years ago, he ostentatiously hired armed guards to patrol the museum perimeter at night and declared ‘enough with token punishments and fancy extenuating circumstances! We need the hard fist of the law here.’

This is all a long way of saying I find it interesting when politics fails to map onto my mainly Anglo-American model, in which younger and highly-educated people reliably vote for parties of the left, and older and less-educated voters support the right.

This trend is also challenged in India, where Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi is just as popular with elite voters as he is with working class Indians. In France, youth support for Marine le Pen has grown with each presidential election. In the 2022 Presidential election, 49% of 25-34 year voters supported Le Pen, more than the 41% of the general population, and 29% of voters over seventy.

Nine Circles will return to the Florentine election next month.

Welcome to Nine Circles, thanks as ever for reading.

📚 Currently reading: ‘In Youth is Pleasure’ by Denton Welch (described to me by one of the excellent and highly knowledgeable booksellers at Mr. B’s in Bath as ‘like an openly gay Evelyn Waugh’).

I knew England’s north-south economic divide was a problem of long standing, but I hadn’t realised until recently that it already existed when the emperor Claudius invaded in 43 AD.

Claudius’ main interest was in conquering the tribes that were sufficiently advanced to be minting their own coins. These were centred in the south-east, and had close cultural links to the Belgic Gauls, some of whom had settled the area. The boundaries of their territory ran from the Humber Estuary near modern-day Hull and followed the river Trent, before heading south and west towards the Bristol Channel, then straight down to Dorset on the southern coast.

These tribal boundaries neatly follow the Jurassic Divide. On the side controlled by the coin-minting tribes were younger sedimentary rocks including sandstones, clays and chalks3, more clement to agriculture, while to the north and west were less productive older shales and igneous rocks4.

Even as the Romans conquered Britannia, better environmental conditions for farming, more advanced economic systems, and closer cultural and trade links with the continent ensured that the south-east far outproduced the rest of the British Isles.

In The Atlantic, Adam Kirsch writes that ‘the close passing of the poetry critics Marjorie Perloff and Helen Vendler is a moment to recognise the end of an era.’

The loss of these towering scholars and critics feels like the definitive end of an era that has been slowly passing for years. In our more populist time, when poetry has won big new audiences by becoming more accessible and more engaged with issues of identity, Vendler and Perloff look like either remote elitists or the last champions of aesthetic complexity, depending on your point of view.

The two were often discussed as a pair, one writer even jokingly referring to the ‘Vendler-Perloff standoff’, but in truth their interests and approaches bore little in common.

Vendler was a traditionalist, championing poets who communicated intimate thoughts and emotions in beautiful, complex language. As a scholar, she focused on clarifying the mechanics of that artistry. Her magnum opus, ‘The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets’, is a feat of ‘close reading’, examining the 154 poems word by word to wring every drop of meaning from them. In analysing ‘Sonnet 23’, for instance, she highlights the 11 appearances of the letter l in the last six lines, arguing that these ‘liquid repeated’ letters are ‘signs of passion’.

For Vendler, poetic form was not just a display of virtuosity, but a way of making language more meaningful. As she wrote in the introduction to her anthology ‘Poems, Poets, Poetry’ (named for the popular introductory class she taught for many years at Harvard), the lyric poem is ‘the most intimate of genres’, whose purpose is to let us ‘into the innermost chamber of another person’s mind’. To achieve that kind of intimacy, the best poets use all the resources of language—not just the meaning of words, but their sounds, rhythms, patterns, and etymological connections.

Perloff ‘was drawn to the avant-garde tradition in modernist literature, which she described in her book ‘Radical Artifice’ as ‘eccentric in its syntax, obscure in its language, and mathematical rather than musical in its form’.’

At a time when television and advertising were making words smooth and empty, she argued that poets had a moral duty to resist by using language disruptively, forcing readers to sit up and pay attention. ‘Poetic discourse’, she wrote, ‘defines itself as that which can violate the system’.

Kirsch goes on to discuss the two critics’ respective backgrounds, and what they had in common, especially as the culture has moved on, as well as what separated them.

See also this lovely appreciation of Vendler in The New Yorker by her former student Nathan Heller.

The most sharply I can recall Vendler ever speaking was when one of us pointed out that some poets had troubled and unhappy lives. ‘Yes, but they are not to be pitied,’ she nearly snapped back. ‘Because they have the much deeper fulfilment of creating lasting works of art.’

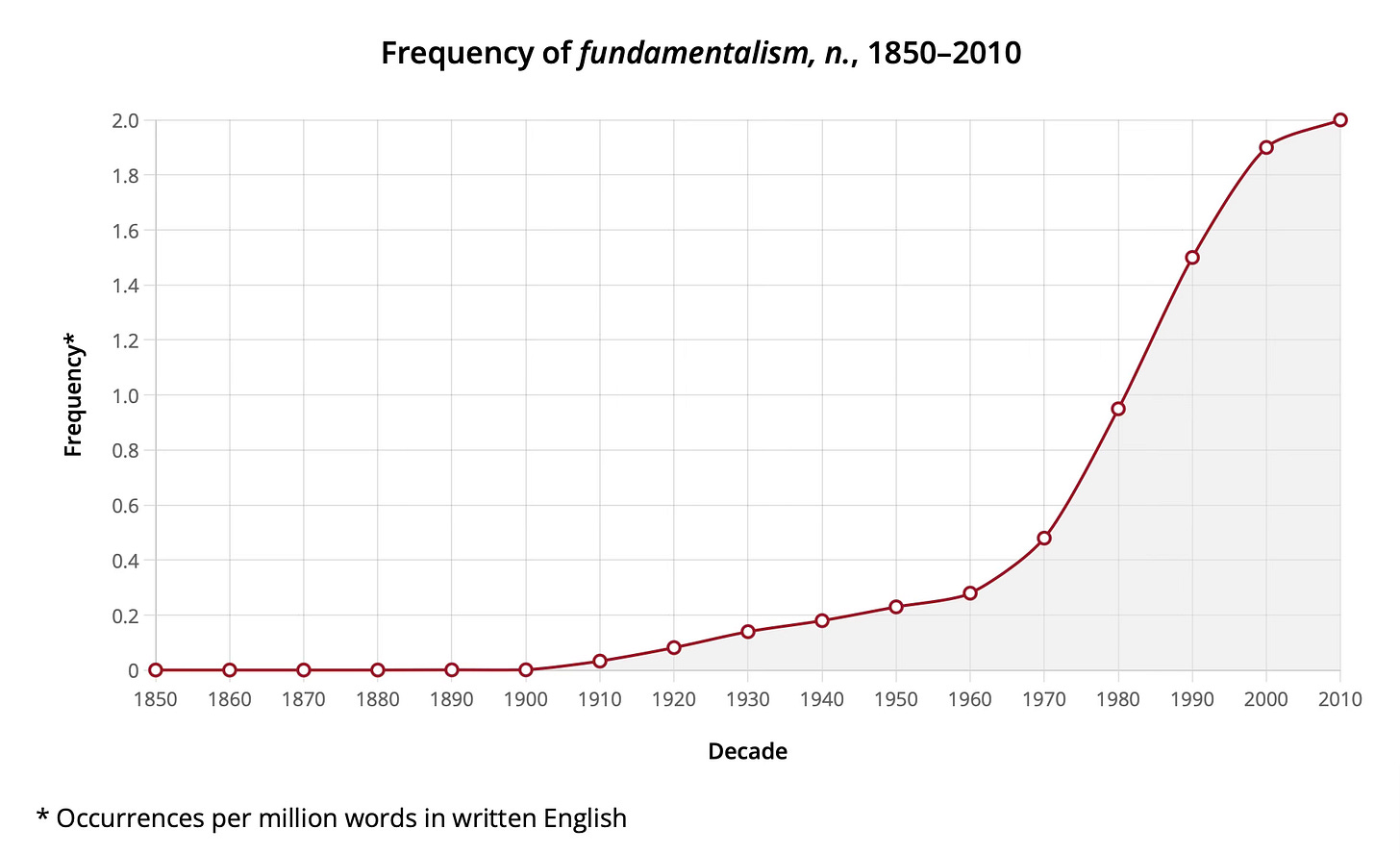

The first recorded use of the word ‘fundamentalism’ is in an 1842 edition of The Catholic Telegraph, a weekly newspaper covering catholicism from Cincinnati, Ohio. The paper doesn’t seem to have an online archive, and I can’t find a copy of the article anywhere, but from what I can gather the term was used pejoratively to describe those who opposed accommodation with such features of modern society as Darwinism and Mormonism.

The frequency of its use steadily increased throughout the twentieth century, and rocketed from the sixties onwards.

‘Opposite, above: All through the house, colour, verve, improvised treasures in happy but anomalous coexistence.’

Brian Dillon’s essay collection ‘Suppose a Sentence’ takes as a prompt for each piece a sentence by a different author, moving chronologically from William Shakespeare to Anne Boyer. My favourite is on Joan Didion and her sentence above, a photo caption from her time in her early twenties working as a research assistant at Vogue.

In Vogue, by the sixties, captions were surprisingly substantial pieces of writing, accorded what might seem a remarkable amount of editorial care. The captions Didion wrote make up a minor, telling aspect of the mythology around her work, though perhaps ‘mythology’ is the wrong word. It is a matter of style, where style is verifiable presence on the page. Didion is frequently described as an exact and exacting writer, her prose like a shiny carapace. At the same time, she has a reputation for being brittle and spectral, barely there. None of this adequately describes her prose. It is usually direct and declarative; it is filled with parallelisms and rhythmic repetitions; there is a wealth of concrete detail.

Reading Dillon’s piece made me want to reread ‘Slouching Toward Bethlehem’ and ‘The White Album’. I’ve been looking for a nice second-hand copy of ‘After Henry’ (her next collection of essays, which is annoyingly out of print in the U.K.) for years.

The essay details so beautifully the care and precision that Didion applied to her writing that it’s hard not to find it inspiring. If you’re into her writing at all, I recommend reading the whole thing. There’s even an element of detective work involved.

Archeologists keep finding copper dodecahedron objects in ancient Roman sites, but nobody knows what they were for, and no contemporary written sources or images reference them. They’ve been found around the western European parts of the empire, but not in Italy itself.

Theories as to their use range from the religious, to objects to test the skill of metalsmiths, perhaps as a way to earn a certain status within a guild, to measuring instruments for distances or sizes.

Here is a description of a recent find in Lincoln by archeologist Samantha Tipper.

Much chortling in the British press about Boris Johnson being turned away from his polling station during yesterday’s local elections, having forgotten to bring the ID required by the law he had himself introduced.

Former Treasury Solicitor5 Jonathan Jones tweeted in response that he had once received a rail penalty fare under regulations that he had himself drafted, and to make matters worse was offered a leaflet explaining the law.

Humorously, ‘Uffizi’ is just Italian for ‘Offices’. The building of the complex was comissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici (not the Cosimo Medici you’re thinking of) in 1560 to consolidate the work of the many guilds and civic committees he controlled into one location.

No, I’m not sure what ‘Aristotelian centrist’ means in practice either.

Fossils from the Jurassic period are often found in these rocks, particularly along the coastline.

Fossils from earlier geological periods, such as the Devonian or Carboniferous are found here.

Confusingly, the Treasury Solicitor is not a solicitor at all, but a Barrister. The title has existed since the seventeenth century, and occupiers of the role since 1878 have been the leaders of the Government Legal Department, where they have a slightly strange mixed role of both helping to draft legislation and representing the government in court.

The term Treasury in this context doesn't solely refer to the Treasury department as we think of it today, but rather to the broader financial and administrative functions of the government, much as the Prime Minister holds the title First Lord of the Treasury.