What is Woke? Baby don't hurt me. Don't hurt me, no more.

Woke? Sinéad O’Connor! Olivia Laing? Frank Auerbach!

I find the term ‘woke’ frustrating. It’s used more often as an insult, as a pejorative, or as an ironic self-description than as a clear label for something like a set of beliefs or a social movement.

Pro- and anti-identity politics people can argue about wokeness interminably without giving an inch to each other, growing in exasperation and frustration, because the term is so amorphous that they can’t even agree on what they’re arguing about.

‘Woke’ has been around for much longer than I knew. It first appeared in African American Vernacular English in the 1940s, when it was used to mean ‘awake to matters of injustice’. It grew in use very slowly over the decades, appearing in a 1971 play and a 2008 song, before exploding in popularity during the 2014 protests in America against police violence and racism.

But while use of the word today certainly implies a specific set of beliefs about race, it also implies beliefs about gender identity, about indigenous communities, about sexism, about climate justice, about nature vs nurture, about how political change happens, about how debates should be conducted, about who has a right to speak or be heard or ‘take up space’, about who can speak on behalf of whom, about the systemic nature of injustice, about what it means to be a good person.

How does holding those beliefs make you ‘woke’, rather than just left-wing or progressive? I think there’s something extra, not in the opinions themselves, but in the way in which they’re held.

In an essay for Harper’s Magazine, Ian Buruma argues that we should understand the belief package of wokeness in the context of the waves of evangelical protestant fervour have swept America over the last couple of centuries. It made me think of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, who argued that all societies, no matter how secular they seem, express their identities in terms that mirror the structure of religious symbols. For Durkheim, the essential nature of religion isn’t found in its doctrine, but in the group practices that demonstrate loyalty and strengthen social bonds: Taking communion together, praying together, singing together, sharing the peace, baptising, giving testimony. And the greatest expression of institutional power I can think of in religion, the moment when faith, identity and obedience are given substance in the world: the confession of sin.

The admission of sin, the disavowal of past behaviour and the public attestation of faith are as foundational to christianity as to wokeness.

Salvation is not sought primarily by belonging to a hierarchical church or synagogue. Protestants have to find their own way to God’s blessing, through self-examination, public testimony, and the performance of actions that demonstrate impeccable virtue. This has to be a constant process. In his famous book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber observed that the Protestant ideal is more demanding than the Catholic aim of gradually accumulating individual good deeds to one’s credit. Sins are not forgiven in rituals of private atonement—cleaning the slate, as it were, for one to sin and be absolved. Rather, salvation lies in ‘a systematic self-control which at every moment stands before the inexorable alternative, chosen or damned.’ God helps those who help themselves. For the chosen, the signalling of virtue can never stop.

Think also about ‘doing the work’ of self-education that allies must take upon themselves. Doesn’t it remind you of the private bible study and rigorous self-examination for traces of sin to be expunged that functions both as a display of loyalty and as a sort of path to mental purity both moral and therapeutic?

This is a powerful social tool: A form of ideology that can both help us to embody the justice we want to see in the world, and lead us to an attitude towards sin ‘not of sympathetic understanding based on consciousness of one’s own weakness, but of hatred and contempt for [the sinner] as an enemy of God bearing the signs of eternal damnation.’

Writing in this magazine in 1964, the historian Richard J. Hofstadter diagnosed the ‘paranoid style’ as a recurrent feature of American politics, whose adherents turned all social conflicts into a ‘spiritual wrestling match between good and evil.’ Some of its earliest manifestations involved Protestant ‘militants’ who were concerned that the country was being infiltrated by ‘minions of the Pope.’

Buruma’s essay goes on to compare the mega-corporations embracing wokeish politics to the Dutch merchants of the 17th century who donated generously to the poor from money made by selling enslaved people. I find it fascinating how quickly corporate HR departments have embraced identity politics, and hilarious when almost absurdly evil companies have progressive DEI policies (we’ll sell weapons to genocidal regimes from our gender-balanced workplace!). I imagine this is what it must have been like to watch the British East India company attempt to perform Christian virtues.

These thoughts are less about the merits of the moral issues wokeness is concerned with, and more designed to shed some light on how we perform those concerns to ourselves and to others. This is such an enormous social and political phenomenon that I think looking at it from many angles is worthwhile.

The angle I’m most confident in looking at all this from is more prosaic: Changing manners.

I once read that the purpose of manners is to prevent anyone from feeling uncomfortable. When we think about classical manners (something that ended somewhere in the nineteen sixties as social mobility increased maybe?), they were characterised by providing a clear and exact rule for how to behave in every situation, from how to refer to someone, to what to wear in a given situation; from which fork to use for which course, to how to conduct a dispute on a matter of honour.

I think our new set of manners are very similar: Insistence on clear rules about pronouns, trigger warnings and land acknowledgements are fundamentally about making sure that as long as everyone follows the rules, nobody has to feel uncomfortable.

The crucial inversion is that while classical manners were concerned with deference towards high-status people, modern etiquette is more often about elaborate deference towards the underprivileged.

Both sets of manners, of course, end up excluding people who don’t know how to speak the language.

I don’t expect the ways we argue about how to be a good person will ever be stable, but my sense is that we’re in a moment of particular flux, balanced between an old moral hierarchy and a new, predicated on a reinvented pyramid of moral worth, where the meek may yet inherit the earth.

Welcome to issue seven of Nine Circles. Thanks so much for being here. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the above, particularly if you think I’m talking total nonsense.

Read on for links to articles about Sinéad O’Connor, Olivia Laing and Frank Auerbach.

Sinéad O’Connor, who died in July (when exactly isn’t public knowledge), almost destroyed her career as a popular musician when she ripped up a picture of Pope John-Paul II on Saturday Night Live in 1992. Ten years later, when the Boston Globe started to publish the utterly appalling stories of clerical sex abuse that set off a global reckoning, some people started to wonder if America owed O’Connor an apology.

I thought I knew the full story of that photo, but there’s so much I didn’t know. Liam Stack in The New York Times writes through both the cultural and personal history leading up to one of the central moments of her life.

In the Ireland of Ms. O’Connor’s youth, politics were dominated by the Catholic Church. For decades, priests at the parish level saw part of their role as protecting the community from sexual promiscuity, homosexuality and unwed mothers and their children.

To do so, they used an unwritten, extralegal power to send women accused of such sins to reform schools, workhouses and other facilities run by Catholic orders.

It was a world with which Ms. O’Connor was intimately familiar, and her experiences in one such facility as a teenager, after enduring years of abuse from her mother, set the stage for the moment on “Saturday Night Live.”

In her memoir, Ms. O’Connor wrote that the picture she tore in half on TV was not just any picture of the pope. It was a picture of the pope’s Mass in the Irish city of Drogheda in 1979, which he dedicated to “the young people of Ireland” and which had drawn 300,000 worshipers.

That same photograph had been the only decoration on her mother’s wall, she wrote, and had looked down on them both as her mother pinned her to the floor and beat her.

After her mother died in a car accident in 1985, she took the picture, determined to someday destroy it. To her it was an object that “represented lies and liars and abuse,” she wrote.

We think we have a censorious culture now, but oh my god if anyone was ever cancelled it was Sinéad O’Connor. What a brave, brave person.

I read Olivia Laing’s novel Crudo a couple of years ago really hoping to like it, but found hardly anything to take from it at all (I do, however, love her Instagram). I wondered if this was because I knew almost nothing about Kathy Acker, who may or may not be the book’s narrator (it is set in 2017, Acker died in 1997), if there was some skeleton key to the whole thing I was missing, or if it just didn’t deserve the considerable hype it received.

Reading Ava Kofman’s review in Dissent makes me want to try again.

It is not an accident that the book feels just like reading Twitter. Laing first announced she was writing the novel in a tweet on August 1, 2017. As she wrote in an essay for Lit Hub, it was conceived as an attempt to register, in real time, that summer’s feeling of “constant interruption, the sense that every piece of unsettling news was abruptly overtaken by another, that there were no visible conclusions to the stories, only a proliferation of bad consequences, waiting implacably a little further down the road.”

Troubled by the chaos of the summer’s news cycle, Laing had been finding it impossible to continue to write the nonfictional meditations on solitude, creativity, and addiction, such as The Lonely City (2016), for which she had become well-known. Crudo emerged as an antidote to her writer’s block. Like social media, it soon became a compulsion. The rules of the experiment were simple, being essentially the same as those followed by people who already post most of their thoughts on the web: react every day (sometimes every hour) to the news, to your friends, to your moods; never revise; publish as soon as possible. Thus Crudo, which means “raw” in Italian.

But the thing that really drew me in is that I’d forgotten that Crudo’s narrator starts to read within the novel about Rachel Cusk, one of my all-time favourite authors. Reading Cusk’s Outline trilogy feels a bit like watching a brilliant surgeon dissect not a body so much as a personality, or a life. Reading Crudo, in contrast, is like having your life, or maybe your personality beamed into your eyes too fast to process. It’s chaotic and unsatisfying, like life. Does that mean it’s a success or a failure? I’m not sure. If I find out, I’ll let you know.

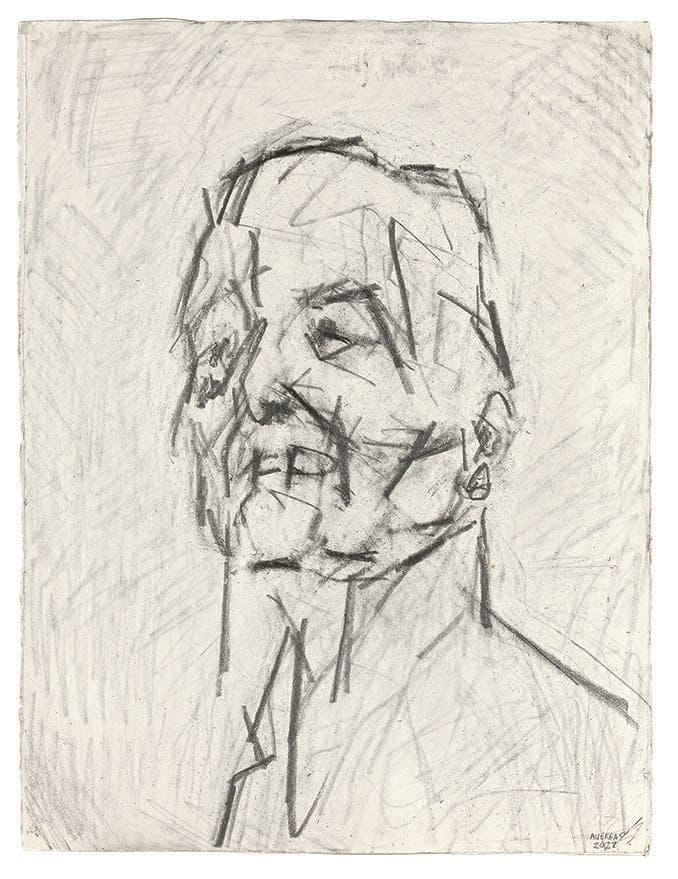

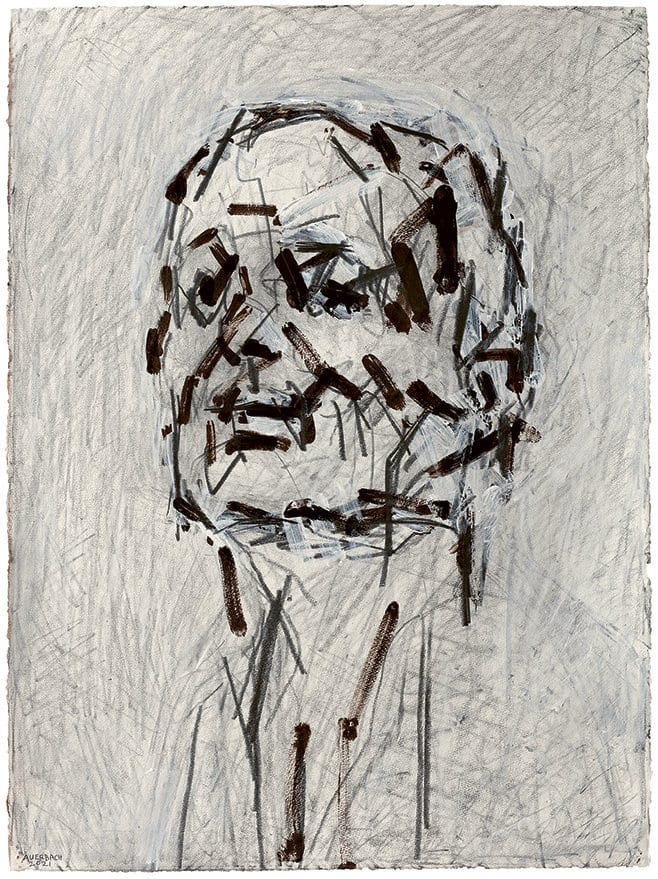

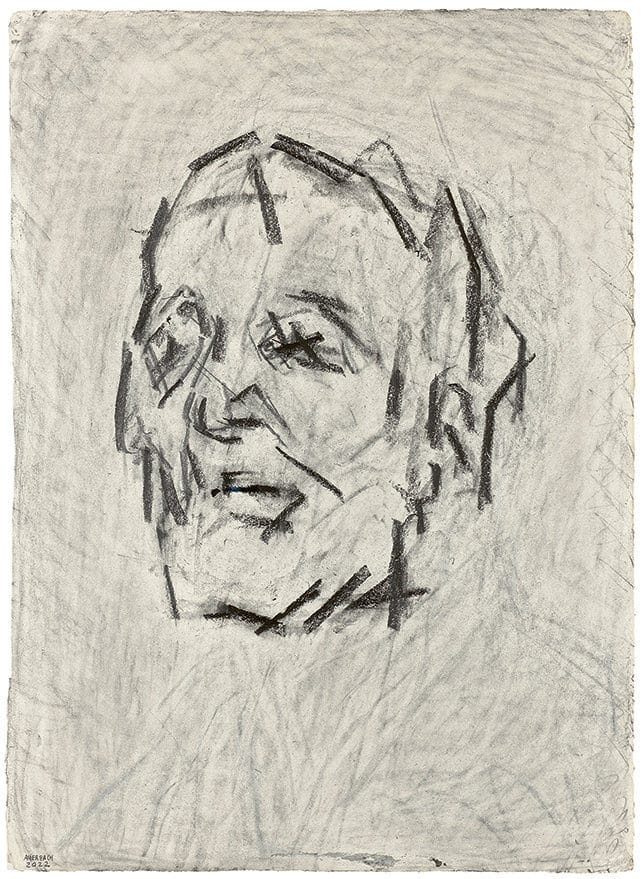

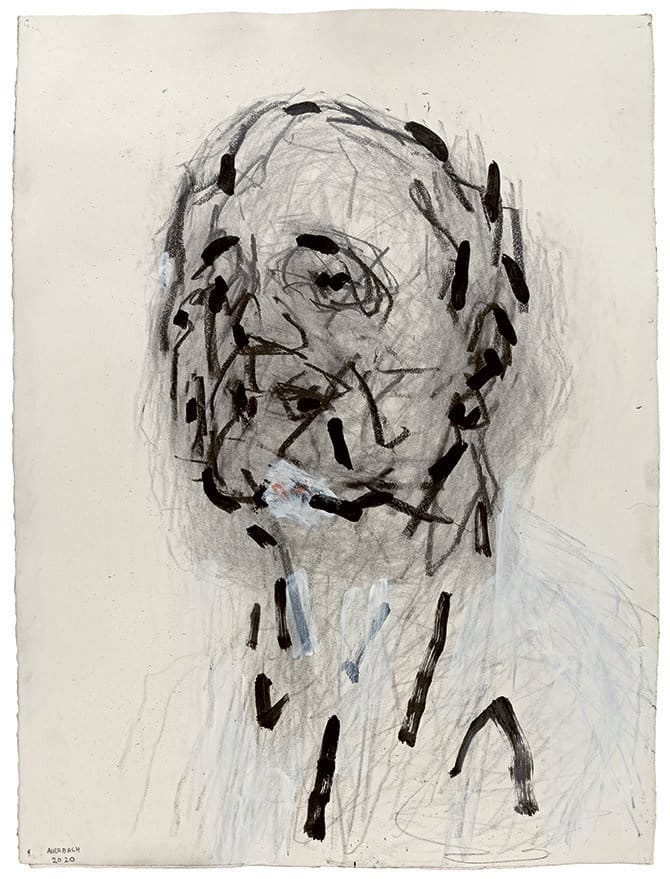

The paintings throughout this issue are from Frank Auerbach’s show of self-portraits that just closed at Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert in London. Auerbach is ninety-two, it’s his first display of new work since 2015, and notable because he had previously hardly ever painted himself. ‘I didn’t find actual formal components of my head all that interesting when I was younger, smoother and less frazzled’, he said. ‘Now that I’ve got bags under my eyes, things are sagging and so on, there’s more material to work with.’

I went months ago to Hazlitt in the heart of St. James’s in central London to see the paintings in person. Arriving at the gallery, where theoretically anyone can go in to have a look, I saw a series of rooms completely empty apart from a very intimidating man in a suit. The door was closed, and it wasn’t clear how I was meant to get in, although it was definitely within opening times. I was desperately frightened that someone would try to talk me into buying something for hundreds of thousands of pounds, and I’d go along with it out of social awkwardness.

Reader, I did not go in.

See you next week x.