If I was to tell you in early 2022 that a disaffected middle-aged man would murder a major world leader that year, that he was convinced his country’s leaders were in a corrupt relationship with an evil cult, that this cult enabled them to win elections, controls a major industrial conglomerate, brainwashes its members, stole all his family money, drove his brother to suicide and ruined his life, you’d probably respond by saying something about the rise of conspiracy theories and the ways young men can often be radicalised on the internet.

If I was to add that he believed the Korean CIA played a significant but still unclear role in the early running of the cult and that it controls a large part of the global sushi trade, maybe you’d shake your head sadly and murmur something about QAnon crazies getting more dangerous.

The victim, speaking to voters on the street when he was shot in the back with a homemade rifle, was former Prime Minister of Japan Shinzo Abe, his assassin was Tetsuya Yamagami, and everything Yamagami accused Abe of was true.

Yamagami’s late mother had been a member of the Unification Church, commonly known as the Moonies after their leader Sun Myung Moon. She had donated everything her family owned to the church, leaving her and her two sons in poverty. Yamagami saw this as the pivotal moment that ruined his life and led his brother to kill himself. This was not an unusual story, U.C. members are often pressured to give crippling donations such that they cannot easily even feed their families. The church, which is based in Korea, often uses Japanese crimes against Korea during the Second World War to shame and motivate members. It’s an effective strategy for starting to estrange cult recruits from mainstream Japanese society because it’s true, and because the hideous crimes Imperial Japan committed against Korean civilians are still not taught in schools, and have never been acknowledged or apologised for by the Japanese state.

How strange then, that the U.C. has been getting away with brainwashing its members and fleecing them of their life savings for decades because of its relationship with the Liberal Democratic Party, the conservative party known for its dominance of post-war Japanese politics and its sympathies with right-wing nationalism.

The U.C., which teaches that Moon was the second coming of Christ, was founded in the 1950s, and from the start was politically powerful in South Korea. Korean intelligence agencies were involved in running it early on, though why remains mysterious and the historical record is incomplete. One possible explanation is they were worried about the new cult of personality in the north, and saw Moon as an anti-communist counterweight.

Regardless of why he was given this special treatment, Moon used these government links to build massive industrial power for himself, buying controlling interests in corporations from arms manufacturers to chemical and construction firms. His companies were even responsible for the popularisation of sushi in America, and to this day control a large part of the global movement of sushi-grade salmon.

While Moon was building his commercial might and his cult in South Korea, in Japan Abe’s grandfather Nobusuke Kishi was ingratiating himself to the Americans. He had been guilty of war crimes as governor of Manchuria, but was released by the post-war American military regime when they realised right-wing nationalists like him could be useful because of their strident anti-communism. Kishi brokered the founding of the Liberal Democratic Party, and served as Prime Minister from 1957 to 1960. The L.D.P. and the U.C. found themselves in the same anti-communist struggles, and both were deeply socially conservative. Despite their wartime animosity, the two organisations found they could help each other.

Church volunteers were more than just foot soldiers for electoral canvassing. The U.C. used their influence with the executives of hundreds of companies to create an informal system of group voting, getting lists of employees and pressuring them to secure the votes of their family members and neighbours. A major part of Japan’s social contract is that ‘salarymen’ will show extreme and lifelong personal loyalty to their employer in exchange for isolation from social and economic risk. It’s unsurprising that a system like this leaves employees vulnerable to political pressure (I highly recommend this blog post by Patrick McKenzie about workplace culture in Japan).

This mutual aid continued for decades. The U.C. indoctrinated and fleeced their members, and they were protected from prosecution because they were highly effective in delivering votes for the L.D.P. In Abe’s final general election campaign, records show that U.C. volunteers made ten times more phone calls to voters than any other group.

Abe’s murder, two years after he retired from office viewed as the most successful Prime Minister of modern Japan, was a cause of national mourning. But as Yamagami’s story leaked out to the public, and as Japan started to see the depth of the alleged corruption, the mood soured. A judicial enquiry is now ongoing, and the current L.D.P. Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida, may have no other way to placate an angry public but to ban the Moonies entirely.

Since Abe’s murder, I’ve tried to understand this situation but have found the western journalism limited and unsatisfying. I’m glad to say that is no longer the case, and to thoroughly recommend this essay by Robert F. Worth in The Atlantic, which takes a long view on the crime, discussing the bizarre history of the cult, the Abe family, and the L.D.P.

Welcome to Issue Ten Nine Circles, where I will not be asking you to transfer your life savings to me. A special welcome to the handful of new subscribers from the Slate Star Codex subreddit. Thank you so much for being here! A special welcome also to my parents, who subscribed this week. This newsletter is therefore on its best behaviour.

Read on for links to the best things I read this week…

📚 Currently reading: Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

The field of neuroscience is having an enormous, bitter row about the nature of consciousness. The proponents of ‘integrated information theory’ and ‘global workspace theory’ are at each others throats, and this piece by Tim Bayne for The Conversation explains why, looking at each of the anti-IIT brigade’s claims in turn.

IIT claims that consciousness is identical to the ‘integrated information’ a system contains, that is the information the system as a whole has beyond that had by its parts.

Many theories start by looking for correlations between events in our minds and events in our brains. Instead, integrated information theory begins with ‘phenomenological axioms’, supposedly self-evident claims about the nature of consciousness. Notoriously, the theory implies consciousness is extremely widespread in nature, and that even very simple systems, such as an inactive grid of computer circuitry, have some degree of consciousness.

Bayne goes on to discuss IIT’s status in neuroscience relative to other rival theories, and makes some suggestions about why it has proven so controversial.

9C favourite Rachel Cusk has a new essay in Harper’s, titled The Spy: On Seeing without being seen. As with everything by Cusk, the end of each paragraph deserves a pause for contemplation. She tells two stories in parallel, of her thoughts upon her mother’s death and funeral, and of a filmmaker known only as ‘E’ who works under a pseudonym. It reads like a short story, to the extent that I kept checking that the magazine had indeed labelled it as an essay.

Highly recommended.

Adam Nagourney, a veteran writer for the New York Times has a new book out: ‘The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Modern Journalism’. A few readers will know that the history of the NYT is a strong candidate for my Mastermind specialist subject, so I’m tremendously excited to read this. It picks up not shortly after the 1969 end of an earlier volume of NYT history, ‘The Kingdom and the Power’ by legendary reporter Gay Talese. There’s a lot to cover, particularly in the last twenty-five years, from the catastrophic scandal caused by the lying fabulist journalist Jayson Blair and the deeply flawed reporting by Judith Miller in the run-up to the Iraq War, to the enormous commercial success of recent history.

Vanity Fair’s Joe Pompeo, an indefatigable chronicler of the Times, interviews Nagourney here.

Here is an extract in Air Mail about Howell Raines first day as Executive Editor: 11th September 2001.

And here is the big New York magazine profile by Shawn McCreesh:

The highest expression of newswriting at the Times has always been what’s called a ‘lede-all.’ As Nagourney writes, a lede-all is ‘an authoritative article that captured a moment in history … they required a combination of command, meticulous organisation, precision, speed, writerly flair and a sense of history and Times style.’ … Nagourney wrote the lede-all the night Obama won…

They’ll never do away with them completely, but at the new Times, the lede-alls are increasingly out of fashion. The emphasis now is on the ‘Live Desk’, which puts out those short-burst news briefings that are thrown together into incoherent, rolling bulletins during particularly newsy moments. The cascading information keeps readers glued to the app, refreshing for more, but many reporters regard it as unrewarding work. Die-hard Times readers can recall trenchant ledes they’ve loved or stories that touched their hearts. No one is ever going to say, ‘Remember that great live briefing’ … When I profiled [current Executive Editor Joe] Kahn last year, he … me they see this as the future of the newsroom. They think that, on breaking news, the “Live Desk” can raise their game to the level of CNN, with its monstrous news-gathering operation… The Times is so big it hardly regards the other newspapers as the competition at this point.

The expression ‘I guess’, meaning that one supposes or agrees, is often used to stereotype Americans in British books and movies, but it was current in England during the seventeenth century, and was no doubt imported by the first North American settlers. Later, that usage went obsolete in England but remained popular in America. An early in-print example comes from the Massachusetts Spy newspaper for February 2, 1798, ‘I guess my husband won’t object to my taking one if they are good and cheap.’ During the nineteenth century, it was a regionalism specific to New England, although it later became common everywhere. To quote the Massachusetts Spy again, for November 8, 1815, “You may hear [a Southerner] say ‘I count’—‘I reckon’—‘I calculate’; but you would as soon hear him blaspheme as guess.”

From Rosemarie Ostler’s new book ‘The United States of English: The American Language from Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century’, extracted in Lapham’s Quarterly. More:

‘Yankee’ is also almost certainly a Dutch contribution. Various theories have been suggested for the word’s origin (for instance, that it’s a Native American mispronunciation of ‘English’), but the most likely one derives the word from ‘Janke’ (pronounced ‘yan-kuh’), a diminutive of ‘John’ that translates as something like ‘little John’. It may have been inspired by ‘John Bull’, a popular nickname of that time for a typical Englishman. Americans were ‘little John Bulls’. At first Yankee referred only to New Englanders, but by the time of the Revolution, when the song ‘Yankee Doodle’ was first heard, the British applied it to all Americans.

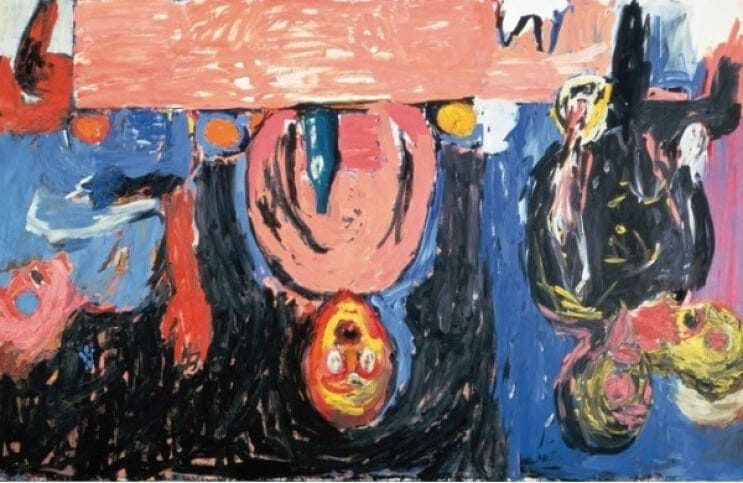

Yes, those paintings are meant to be upside down. Georg Baselitz first became known as a painter in the sixties, and has been painting things upside down since nineteen sixty-nine.

Thanks as ever for reading.

See you next Sunday x