The world thinks it knows who Joe Biden is. A man who has near-continuously held public office since 1971: Elected at twenty-eight to New Castle County Council in Delaware, then straight into the Senate at thirty, where he spent thirty-six years, before eight as Vice President, four years opposing Trump and running for President (while bitterly regretting not standing against Hilary and nursing a simmering resentment that Obama prevented him from challenging her for the nomination), and now two and a half years as America’s oldest ever president.

Fifty-two years of folksy anecdotes, deals across the aisle, and deep irritation with brainy Ivy League types thinking they know how to do politics better than him.

And decades apart, moments of genuine personal tragedy, followed by very public mourning that enabled Biden to take on a strange sort of role as mourner-in-chief during moments of national grief.

He’d like us to think that what you see is what you get: A good old Irish fellow from Scranton who came into politics as a civil rights activist, had a steady hand on the tiller of American foreign policy for decades, and rose to the moment when democracy was threatened.

Behind this public face is a man who is in some ways uncomplicated, but is in others more of a mystery than often supposed. This is a man who believes himself to be the indispensable politician of recent world history: The only person who could beat Trump, end America’s wars in the Middle East, enact a massive green transformation of the economy in a 50-50 Senate, re-orient towards China and bring down the temperature of a boiling national mood. A man who as president is still deeply bothered when he feels like he’s being talked down to by experts and advisors. A man who was very hurt when Obama dissuaded him from standing against Hilary for the 2016 nomination. A man who can’t help himself but run for President again, in the knowledge that he’d be taking the oath of office at eighty-two, and serving until eighty-six.

What is behind this self-belief? In his new book The Last Politician: Inside Joe Biden’s White House and the Battle for America’s Future, Franklin Foer argues that for all we’ve been exposed to him, Biden is a strangely unexamined character. In part this is a function of the insularity of his top team. Advisors like Ron Klein, Anita Dunn, Steve Ricchetti, Bruce Reed and Mike Donilon have been working for him since the eighties. Whatever rivalries they once had are long since worked out, and since they have no need to undermine each other, they don’t tend to leak to the press, so we know far less about internal deliberations and Biden’s thinking than we did about Trump’s or Obama’s.

After a glut of highly commercially successful books of reportage during the Trump era, the Biden library so far is looking a little thin. I’m going to grab a copy of The Last Politician after payday (London rent is ruinously expensive, sigh) and might share a list of things I learned in a future edition of this newsletter, but for now let me point you to this extract in The Atlantic covering the period of the withdrawal from Kabul, and this interview Foer gives with Ryan Lizza of Politico, which 100% sold me on the value of trying to more closely understand Joe from Scranton.

Helen Lewis writes in The Atlantic about the problem of ever more fawning blurbs on book covers. Cronyism, exaggeration and cliché are everywhere:

Even the most minor title now comes garlanded with quotes hailing it as the most important book since the Bible, while authors report getting so many requests that some are opting out of the practice altogether. Publishers have begun to despair of blurbs, too. ‘You only need to look at the jackets from the 1990s or 2000s to see that even most debut novelists didn’t have them, or had only one or two genuinely high-quality ones,’ Mark Richards, the publisher of the independent Swift Press, told me. ‘But what happened was an arms race. People figured out that they helped, so more effort was put into getting them, until a point was reached where they didn’t necessarily make any positive difference; it’s just that not having them would likely ruin a book’s chances.’

HL argues that two things are driving blurb inflation: The decline in the power of critics relative to online user reviews and influencers, and a superstar system where a small number of titles provide the majority of sales for publishers.

Too many books are being published at a moment when the traditional gatekeepers at newspaper and magazine literary review sections are vanishing, meaning blurbs aren’t extracted from reviews as much as they’re solicited directly from authors and celebrities.

And that reveals another dirty secret of the blurb: They’re not addressed to you. ‘The biggest thing to understand is that blurbs aren’t principally, or even really at all, aimed at the consumer,’ Richards told me via email. ‘They are instead aimed at literary editors and buyers for the bookstores—in a sea of new books, having blurbs from, ideally, lots of famous writers will make it more likely that they will review/stock your book.’

This does possibly solve a mystery I’ve long wondered about: Why I so often see blurbs where the blurber says something like ‘fascinating… I devoured it in one sitting’ on a two-hundred and fifty page book that no normal person could read in one go. Is it directed at literary editors and buyers, to suggest that they can get through it quickly to hit their deadlines?

In my reporting for this piece, certain names repeatedly came up as prolific blurbers. ‘Salman Rushdie, Colm Tóibín, even the reclusive J. M. Coetzee make frequent appearances, so many that you wonder how they find time to read all these books and keep up the day job too,’ the critic John Self told me. The British polymath Stephen Fry, meanwhile, ‘has hilariously blurbed about half of all books published in the U.K.,’ said James Marriott of the London Times. His brand is cerebral, patrician, and politically unchallenging. ‘To me his endorsement means nothing, but I wonder how far casual bookshop visitors get that he puts his name on everything.’

The whole piece is worth reading just for coining the term ‘blurblejerk’.

Why is it that a clock has twelve hours, an hour has sixty minutes, and a minute has sixty seconds? I have long thought this is a stupid system, and that we could make everything much easier by having ten hours in a day, ten days in a week, and ten weeks in a month (there would therefore be five and a bit months in a year, so it’s not perfectly neat, but I think this would still be better than what we have now, and it would have the advantage that our smaller number of months would more directly map onto the seasons).

Keith Houston answers my questions in Lapham’s Quarterly, starting by looking at the Lemobmo bone: The earliest known tool for counting (it’s 42,000 years old).

Counting in the prehistoric world would have been intimately bound to the actual, not the abstract. Some languages still bear traces of this: a speaker of Fijian may say doko to mean ‘one hundred mulberry bushes,’ but also koro to mean ‘one hundred coconuts.’ Germans will talk about a Faden, meaning a length of thread about the same width as an adult’s outstretched arms. The Japanese count different kinds of things in different ways: there are separate sequences of cardinal numbers for books; for other bundles of paper such as magazines and newspapers; for cars, appliances, bicycles, and similar machines; for animals and demons; for long, thin objects such as pencils or rivers; for small, round objects; for people; and more.

Basically, it’s all about how the Mesopotamians figured out counting:

The Mesopotamians’ unique counting method is thought to come from a mix of a duodecimal system that used the twelve finger joints of one hand and a quinary system that used the five fingers of the other. By pointing at one of the left hand’s twelve joints with one of the right hand’s five digits, or, perhaps, by counting to twelve with the thumb of one hand and recording multiples of twelve with the digits of the other, it is possible to represent any number from 1 to 60. However it worked, the Mesopotamians’ anatomical calculator was a thing of exceptional elegance, and the numbers they counted with it echo through history. It is no coincidence that a clock has twelve hours, an hour has sixty minutes, and a minute has sixty seconds.

If you think my argument that we should use a time and date system with base ten is stupid, I’ll grant you that it’s controversial. Here, then is something that’s just obviously true: We should stop calling events between 1600 and 1699 the seventeenth century. It is needlessly confusing. From now on, the years between 1200 and 1299 are the twelfth century, between 1900 and 1999 is the nineteenth century, etc. This will be much easier for everyone.

Some of you who do not recognise the simple good sense of this may object by asking ‘what of the years between 0 and 999?’

To which I simply say that that is obviously the zeroth century.

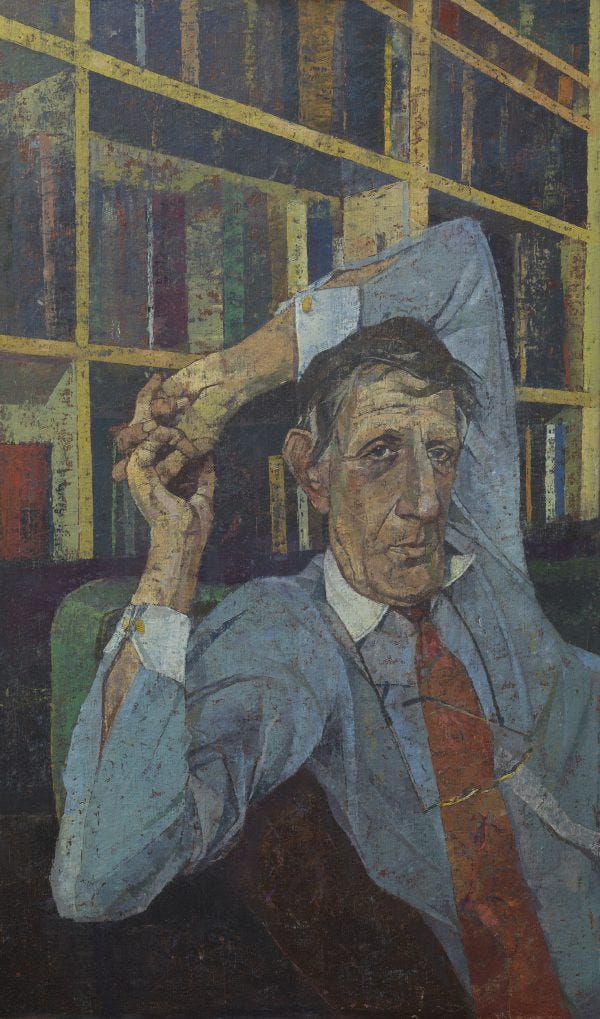

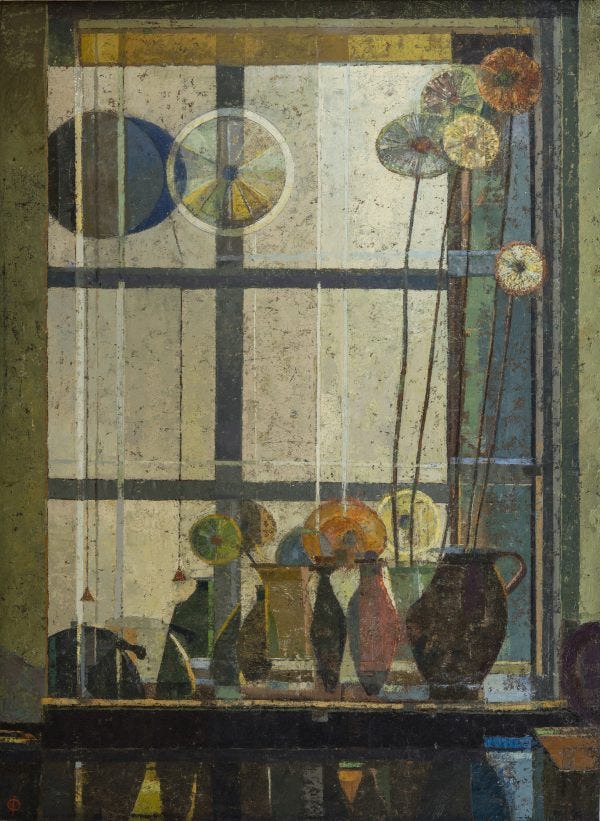

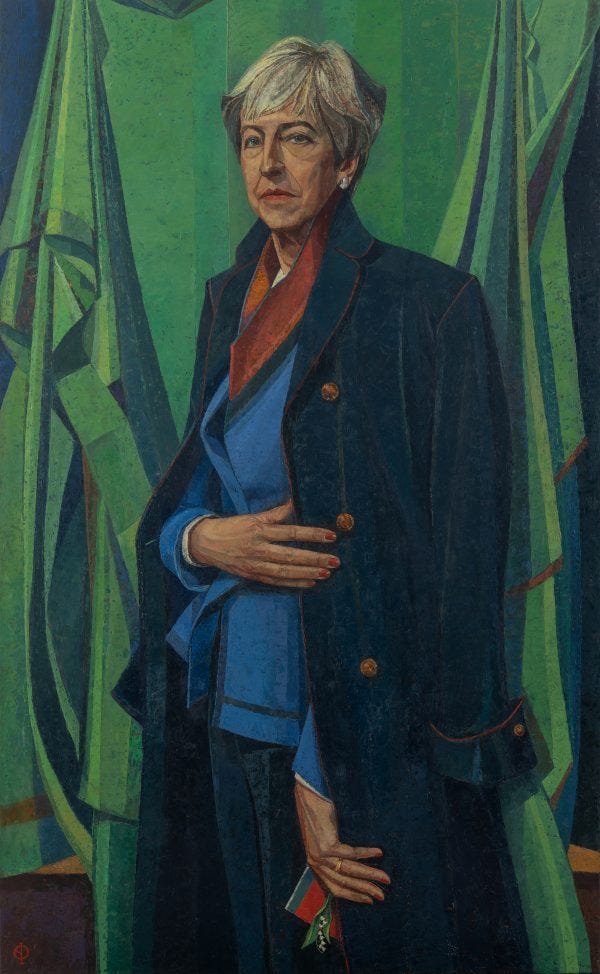

I was surprised to find that I really like the new official portrait of Theresa May commissioned of the Houses of Parliament. Saied Dai has her holding Lily-of-the-valley, also known as May Bells or Our Lady’s Tears. Almost too apt. His paintings are throughout this edition.

See you next week. x

I enjoyed reading this. Especially about numbers, counting and your idea about centuries. The topic of reviews on books is topical for me as I have been asked to read and review a book. I have given a brief review as there was a launch and and waiting until I get time to read the rest to give my full review. Unfortunately the beginning of the book was the best bit and if I had waited my review would have been different. I was hoping it would help parents wading through books on sensory issues and be able to know what this is about but I am not sure that my initial review will do this accurately. Thanks Dan!