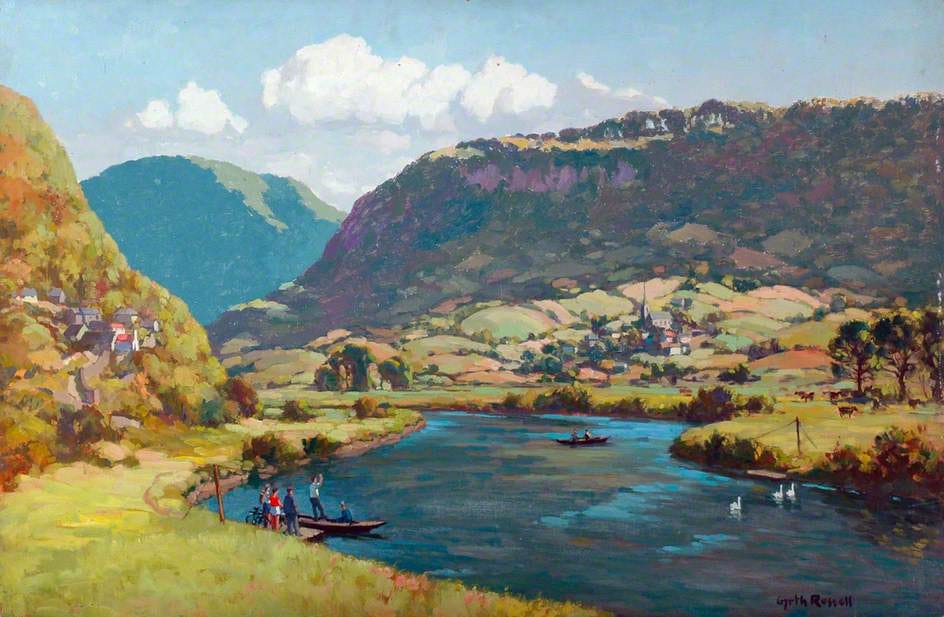

Welcome to issue eight of Nine Circles. This evening’s edition brings you warm greetings from the Wye valley in mid Wales, where we’re staying with Rosie’s mum Becky, before heading on to the west Wales coast tomorrow.

One of the things I most enjoyed reading this week was Divine Comedy by Lamorna Ash for the Guardian: A story a standup comedy double act who interrogated life using absurdist jokes and sketches, but whose questions got more and more fundamental, leading them both to a vocation in the Church of England priesthood. The piece goes on to describe the transformations they experienced, the bafflement of some of their peers, and their ongoing religious journeys. It also serves as a portrait of the wonderfully, eccentrically English world of the modern C of E priesthood, running past characters like the brilliantly named Brutus Green, a vicar in Putney.

I didn’t know this:

In the Book of Revelation, it is prophesied that Christ will return once more to Earth from the east. Most Christians are buried facing east for this reason, to rise from the soil at the second coming and see their saviour face to face. Priests and bishops, however, are buried facing west, to stand, as they did in life, before their congregations, guiding them onwards into eternity.

Highly recommended.

Peter Kellner, the dean of British political opinion researchers, writes on his blog The Politics Counter about how socialism in the nineties and two-thousands evolved from an ideology to an ethic. It’s a story centred around a documentary Kellner worked on with Neil Kinnock after he’d lost the 1992 election to John Major, but saved the Labour Party from oblivion in the process.

For some weeks we struggled to find a new, succinct definition of socialist ideology that would be fit for [the show]. It was Neil who solved the problem, and with the utmost simplicity. Modern socialism should not be an ideology at all, but an ethic. The party’s long-term aims should leave out any reference to the ownership of businesses. The relationship between labour, capital and the state should be determined by the circumstances of the day. The party should abandon the goal, set out in 1918 and inscribed on each membership card, of ‘common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange.’ Instead, it should define itself in terms of liberty, social justice and opportunity for all.

The essay takes the reader quickly through the history of the twentieth century from the writing in 1917 of the famous Clause Four of the Labour Party constitution, committing it to the nationalisation of industry, through to its deletion by Tony Blair in a famous display of dominance over the party in 1995.

More that I didn’t know:

Hugh Gaitskell attempted to [delete it]. He succeeded Attlee as party leader in 1955, four years into thirteen years of Conservative rule. In 1960, following Labour’s third general election defeat, he told the party’s annual conference that he wanted to amend the party’s aims. The delegates thwarted him. A messy procedural deal prevented a vote in which Gaitskell would have suffered an acutely embarrassing defeat. Instead the issue was dropped. It would be more than thirty years before it would be picked up again.

I loved reading A Marriage of Minds, Rachel Aviv's profile of the philosopher Agnes Callard (whose writing appeared in a previous edition of Nine Circles arguing trollishly that going on holiday is in fact bad) in the New Yorker. Her divorce, re-marriage and ongoing relationship have become both subjects of her philosophy, and a way in which she enacts her philosophical ideas in the world. Her ex-husband, the philosopher Ben Callard, is quoted in the piece as saying 'I think to an unusual degree Agnes sort of lives what she thinks and thinks what she lives.'

The piece ends up posing pretty broad questions about the point of marriage and asks what exactly we can expect from our long-term romantic relationships. Just as you’re starting to worry that all the philosophy in the essay is an excuse to gawk at people making pretty wild life decisions, Aviv drops in this paragraph:

In ‘Parallel Lives’, a study of five couples in the Victorian era, the literary critic Phyllis Rose observes that we tend to disparage talk about marriage as gossip. ‘But gossip may be the beginning of moral inquiry, the low end of the platonic ladder which leads to self-understanding,’ she writes. ‘We are desperate for information about how other people live because we want to know how to live ourselves, yet we are taught to see this desire as an illegitimate form of prying.’ Rose describes marriage as a political experience and argues that talking about it should be taken as seriously as conversations about national elections: ‘Cultural pressure to avoid such talk as ‘gossip’ ought to be resisted, in a spirit of good citizenship.’

Displaying characteristic wisdom, my father would probably say that everyone described herein is thinking too much.

Thanks for reading Nine Circles.

See you next week. x

Wow can’t believe you managed to get that done after such a day of work and fatherhood! Marriage has always interested me as it would look on the outside that I shouldn’t agree with it (3 times lucky) but to be married feels so different to not. The feeling of security and what is says to others about commitment is comforting to me. Now I have got it right it is everything! Much more important to me than politics :)